Key Considerations for Marijuana Legalization

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

SJ67 and HJ130 from the 2020 General Assembly directed JLARC to review how the state could legalize marijuana, with a focus on how the prior harm to disproportionately affected individuals and communities can be redressed through legalization.

ABOUT MARIJUANA LEGALIZATION

Because of its intoxicating effects, marijuana is an illegal substance under federal law. Medical use of marijuana is now legal in many states, including Virginia. Marijuana has been legalized for adult use in 15 other states and the District of Columbia, and most of these states have authorized commercial sale of marijuana.

WHAT WE FOUND

Legalizing marijuana would require several legislative decisions

If Virginia legalizes marijuana, the General Assembly would need to make several policy choices. The General Assembly would need to determine legal limits on the amount of marijuana an individual could possess; where marijuana could legally be smoked or consumed; the legal age for marijuana use; and whether to allow individuals to grow their own plants. Legislators would also need to determine whether to adjust existing penalties for illegal distribution and possession above the legal amount. In addition, the legislature would need to address consequences for marijuana use in vehicles, driving under the influence of marijuana, and possession and use by youth and other individuals not of-age.

Creating a commercial marijuana market would entail issuing licenses for five types of operations

The General Assembly could authorize the development of a statewide market for commercial adult use marijuana sales. Virginia would need to issue licenses for five types of major business operations that comprise the marijuana industry: cultivation, processing, distribution, retail sales, and testing.

Other states and countries have taken several approaches to structuring their commercial markets, and Virginia could use lessons learned from these experiences. Virginia could allow “vertically integrated” businesses, in which a single business can be licensed to cultivate, process, distribute, and sell marijuana at retail. Virginia could instead prohibit vertical integration by not allowing businesses with a retail license to obtain licenses for cultivation or processing. This could provide greater opportunity for small businesses to participate in the marijuana market. Regardless of the market structure chosen, licensed testing labs would be needed to test products for purity and quality. These labs should be independent of any other marijuana operations.

The number of licenses issued would depend on demand for legal marijuana. Based on the commercial marijuana markets in other states, Virginia could eventually issue between 100 and 800 cultivation licenses, 30 and 150 processing or distribution licenses, and 200 and 600 retail licenses. The size and number of cultivators would need to be limited to prevent over-consolidation of the market and over-supply of marijuana. In addition, the number of retail licenses should be capped to prevent the over-proliferation of retail stores.

State could allow localities to opt out of commercial market, and current medical marijuana businesses should be allowed to participate

States with commercial marijuana markets typically give localities some authority over marijuana businesses. If Virginia created a commercial market, it could allow localities to opt out of it. A JLARC survey suggests that a majority of localities in Northern Virginia and Tidewater would be likely to participate in a commercial market, but localities in Southwest and Southern Virginia may be less interested in participating. Localities should be able to determine the number of marijuana retail establishments to license in their jurisdictions and be able to apply existing zoning processes and other local requirements that apply to businesses.

Virginia’s currently licensed medical marijuana businesses should be allowed to participate in a commercial market but be required to meet the same requirements as other businesses. Medical marijuana businesses should not be allowed to enter the commercial market before other businesses, based on lessons learned in other states. Over the long term, the goal should be to merge the two markets under a single regulator, license structure, and set of regulations.

Virginia could choose to use legalization to address prior disproportionality in marijuana enforcement

Black Virginians comprise a disproportionately high percentage of individuals arrested and convicted of marijuana offenses. From 2010–2019, the average arrest rate of Black individuals for marijuana possession was 3.5 times higher than the arrest rate for white individuals (and significantly higher than arrest rates for other racial or ethnic groups). Black individuals were also convicted at a much higher rate—3.9 times higher than white individuals.

In other states that have created commercial marijuana markets, relatively few Black individuals have benefited from the establishment of commercial marijuana markets. Industry statistics show the vast majority of current marijuana business owners are white, and there are few Black-owned marijuana businesses.

To redress past disproportionality in marijuana enforcement and ensure Black Virginians have an opportunity to benefit from the new commercial market, Virginia could implement several “social equity” initiatives. Other states are increasingly attempting to achieve social equity goals through their commercial markets. No state, though, has been able to fully achieve these goals, and several are revising their approaches to improve their effectiveness.

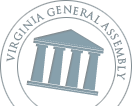

The state could consider several approaches to address social equity. It could provide ownership opportunities for social equity businesses by establishing a licensing process and business assistance program needed for these businesses to effectively compete with well-established, larger marijuana businesses. The state could also take measures to maximize employment opportunities for social equity individuals in marijuana and other related businesses. Additionally, the state could allocate marijuana tax revenue to existing programs in communities most affected by drugs and the enforcement of drug laws or create a new community reinvestment program to fund initiatives in these communities. These options have varying potential benefits and costs (table).

Virginia would need to take measures to mitigate unintended negative public health consequences

The full health implications of marijuana legalization are not fully understood, but marijuana use does present several public health risks. Marijuana is an intoxicating substance, and people who drive after using marijuana can be at an increased risk of a vehicle accident. People who overconsume marijuana can suffer from several temporary problems such as severe anxiety, vomiting, or drowsiness. Marijuana consumption may encourage the use of other substances, such as alcohol, which can compound marijuana’s negative effects. Research shows likely associations between habitual marijuana use and several negative health outcomes ranging from physical health problems, such as mild respiratory issues, to cognitive and mental health issues.

If marijuana is legalized, Virginia would need to establish prevention efforts to inform both adults and youth about the risks associated with marijuana consumption. The state would need to develop regulations addressing product potency, packaging, and labeling. The state would also need to set restrictions on advertising. Product requirements and advertising restrictions should help to reduce the appeal of marijuana to youth and help prevent accidental consumption and overconsumption. Other states have similar requirements, and they also typically conduct statewide informational prevention campaigns to deter youth use. Virginia could create its own statewide youth prevention campaign while also ensuring adequate funding is provided to community-based substance use prevention programs.

Virginia would need to grant regulatory authority to VABC or create a new agency to regulate the commercial marijuana market

Virginia should vest authority for regulating commercial marijuana with a single board and agency. Regulators in other states uniformly stressed that this is the best approach because it is simpler for both the regulator and the regulated industry. By having one main regulatory body, the state could eliminate duplicative oversight or potential gray areas with other regulators. It is also easier for the regulator to carry out basic functions, such as setting regulations and issuing licenses, because there is less need to coordinate with other regulators. The regulated industry benefits because license holders would not have to work with more than one regulator.

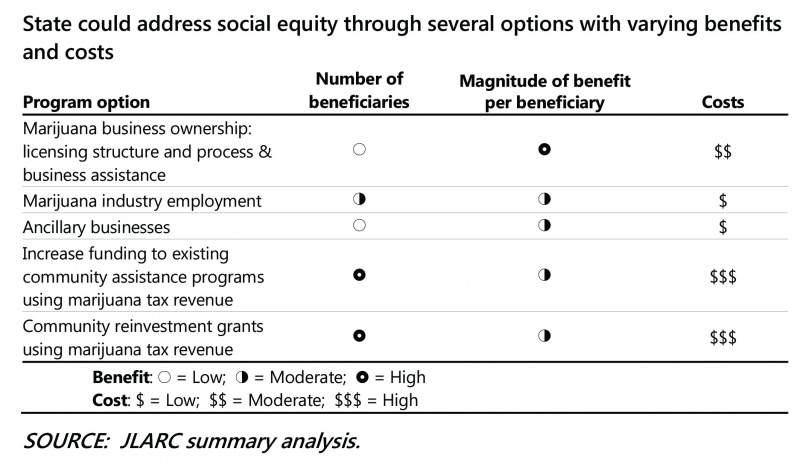

Virginia could grant regulatory authority for commercial marijuana to an existing agency—the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority (VABC)—or it could create a new board and agency. There are tradeoffs to each approach (table). For example, because of its existing management and administrative infrastructure, VABC would need fewer additional staff than a new agency. VABC could need $7–$9 million annually to hire approximately 85 to 105 staff. Creating a new agency could require $9–$12 million annually to hire approximately 110 to 140 staff. VABC would also be able to implement its new responsibilities faster than a new agency.

A new agency would be solely focused on regulating marijuana. In addition, it could more easily provide the appropriate emphasis for a social equity program than VABC, which has a broad range of responsibilities. Moreover, a new agency could be directed to focus solely on regulatory compliance and not have law enforcement responsibilities, if the state prefers this approach.

Taxing commercial marijuana sales would eventually produce substantial revenue

Most states with commercial marijuana markets tax marijuana retail sales, and total taxation is typically between 20 and 30 percent of the retail sales value. Virginia could implement a total combined tax rate of 25 to 30 percent comprising (i) a new 20 to 25 percent marijuana retail sales tax and (ii) the existing 5.3 percent standard sales tax. A total rate of 30 percent would be at the upper end of the range of other states’ marijuana tax rates. Colorado, though, has a combined marijuana tax rate of around 30 percent and has a strong marijuana market. Virginia could also tax easier-to-consume products, such as edibles, and higher potency products at higher rates than marijuana flower.

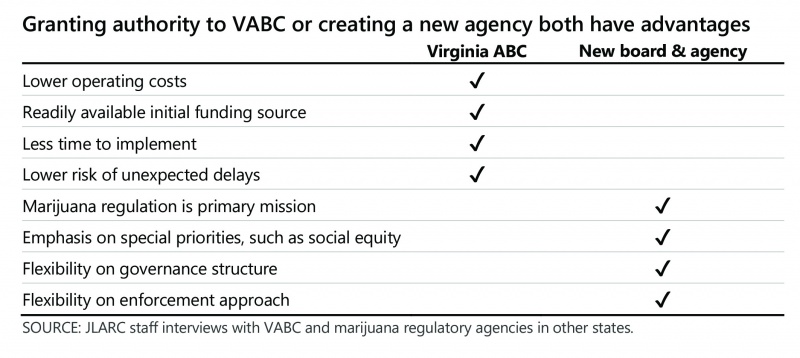

A legalized commercial market could generate substantial revenue for state and local governments, once the market matures. Depending on demand and the tax rate selected, commercial marijuana could produce $31–$62 million during the first full year of sales, depending on the state’s chosen tax rate (figure). By the fifth year of sales, commercial marijuana could produce $154–$308 million in tax revenue.

Revenue would increase as commercial market matures but would vary depending on demand in legal market and tax rate

A commercial marijuana market could create thousands of new jobs, many at lower than median wage levels

Virginia’s marijuana industry could eventually be responsible for creating approximately 11,000 to more than 18,000 jobs (0.3 to 0.5 percent of the state’s workforce). These jobs would not be created all at once; it would take several years to reach those employment levels. Marijuana industry employment would most likely be concentrated in the state’s most populous areas.

Jobs in the legal marijuana industry can pay a wide range of wages, but the majority would likely pay below Virginia’s median wage. Retail marijuana businesses would employ “budtenders,” who sell marijuana to consumers. Cultivators and processors employ growers, technicians, and “trimmers,” who trim and weigh marijuana plants. Given the number of lower wage jobs, the median wage in Virginia’s marijuana industry would probably be less than Virginia’s median wage.

Authorizing and implementing a commerical market would take two or more years, but revenue would far exceed costs after sales start

Depending on exactly how the state implements a commercial market, it would take about two to two-and-a-half years to do so after passing legislation legalizing marijuana. The regulatory agency would need to hire agency staff, draft regulations, and issue licenses. If a new regulatory agency were established, it would need additional time to hire its executive staff and establish basic organizational and administrative functions. Marijuana business license holders would then need to establish their operations.

As a commercial marijuana market matures, retail marijuana sales would produce substantially more revenue than associated state costs. The costs of a state regulatory agency, public health programs, and social equity programs could total approximately $10–$16 million annually. Retail sales would begin, at the earliest, two years after legislation is passed. In the interim, the state regulatory agency could raise several million in licensing fees that could partially offset operational costs. After commercial sales started, marijuana sales tax revenues could cover remaining costs. If the state set the marijuana sales tax at 25 percent, there would eventually be an estimated $177–$300 million in net tax revenue after operational costs ($147–$250 million if the marijuana sales tax rate was set at 20 percent).

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

JLARC staff developed recommendations and policy options for the General Assembly to consider if it legalizes marijuana. The complete list of recommendations and options is available here.