Virginia's Correctional Education Programs

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2024, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission directed staff to review Virginia’s correctional education and vocational training programs. Staff were also directed to review the educational programs in Virginia’s jails and consider the feasibility and effectiveness of expanding such programming.

ABOUT VIRGINIA'S CORRECTIONAL EDUCATION

State law requires the DOC director to establish education programs for inmates, including a “functional literacy program” for individuals testing below the 12th-grade level. DOC is also required to provide elementary, secondary, postsecondary, career and technical education, adult education, and special education programs. Educational programs at DOC facilities are primarily funded by the state and constitute a relatively small proportion (about 2 percent) of DOC’s overall budget.

WHAT WE FOUND

Providing educational programs in a correctional setting is challenging

The unique security demands and staffing challenges of a correctional environment impact the delivery of educational programming. Consistent programming requires enough correctional officers (COs) to manage inmate movement to and from classrooms, prevent the unsafe use of or access to certain classroom equipment, and de-escalate conflicts arising in classrooms. However, the Virginia Department of Corrections (DOC) faces a critical, longstanding CO shortage, with 1,534 vacancies as of July 2025, and some facilities having CO vacancies of more than 30 percent. Insufficient security personnel or security incidents—like the inmate attacks on several Wallens Ridge State Prison COs in 2025—can lead to security lockdowns and, therefore, class cancellations. Security requirements can also limit which classroom materials and IT resources can be used for instruction.

Furthermore, inmates often have mental health or substance use disorders that mandate treatment, which take precedence over classroom attendance and limit their ability to participate in educational programming fully. DOC staff also must strategically select which inmates can be placed in a classroom together to prevent potentially disruptive conflicts.

Despite these challenges, correctional education programs appear to be effective at improving post-release outcomes (e.g., higher employment and wages, lower recidivism), based on national research and Virginia-specific analysis.

DOC assessments show that about 40 percent of inmates need educational programming to reduce their likelihood of reoffending

DOC policy specifies that one of the purposes of its programming, including educational programming, is to reduce inmates’ recidivism risk, and national research indicates an association between educational program participation and reduced recidivism. DOC uses the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) assessment to estimate each inmate’s recidivism risk level and evaluate their educational or vocational programming needs. In February 2025, about 9,200 (40 percent) of DOC’s roughly 22,700 state-responsible inmates had been determined to have a “probable” or “highly probable” need for educational or vocational programs to reduce their risk of reoffending.

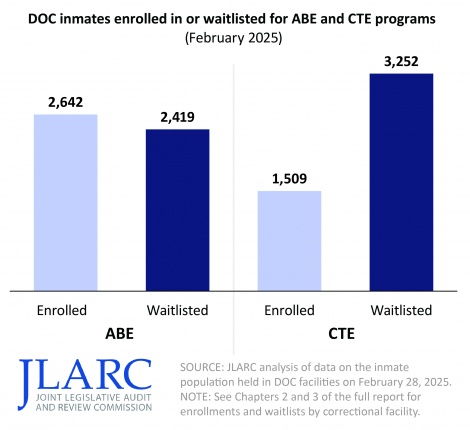

Virginia inmates who participate in correctional education have somewhat better employment and wage outcomes

JLARC staff’s analysis of employment and wage outcomes for correctional education program participants found that inmates who participated in either adult basic education (ABE), career and technical education (CTE), or postsecondary programming were more likely to be employed for the first two quarters after their release from DOC than other similarly motivated inmates (e.g., inmates on a program waitlist who never enrolled). Inmates who participated in CTE or postsecondary programming also earned higher wages than non-participants.

Post-release employment rates of correctional education program participants vs. non-participants

JLARC staff’s analysis also found that participants in ABE, CTE, and postsecondary programming had lower rearrest rates within the first 12 months after their release. Although the relationship between program participation and fewer rearrests was not statistically significant, national research has shown that correctional education programs can reduce recidivism. For example, a RAND meta-analysis study of correctional education outcomes in 2018 estimated that ABE programs can reduce the likelihood of recidivism by about 30 percent.

Small proportion of DOC inmates participate in correctional education, but eligibility and demand significantly exceed capacity

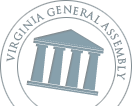

While a relatively small proportion of inmates participate in ABE or CTE programs, there is significant unmet demand for these programs because of constraints like staffing, space, and technology. Of inmates released in 2024, about 19 percent participated in ABE, and 16 percent participated in CTE. Both programs have extensive waitlists, and a large number were never enrolled before their release.

About a third of DOC inmates (7,539) lack a high school credential, and DOC policy requires inmates without a high school credential to participate in ABE programming, with some exceptions. Only about half of those inmates were enrolled in ABE programming in February 2025, with roughly the same number on an ABE waitlist.

CTE and ABE programs have extensive waitlists

Furthermore, in February 2025, over 3,000 inmates were on a CTE program waitlist—more than double the number of inmates enrolled at the time. The largest waitlists were for the Custodial Maintenance, Electrical, Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning & Refrigeration, Welding, and Masonry programs. In 2024, 623 inmates released from a DOC facility were on a CTE waitlist but were unable to participate in those programs before release.

DOC does not consider recidivism risk in educational enrollment decisions, even though reducing recidivism is a primary goal

DOC considers inmates’ recidivism risks and assesses programming needs in enrollment decisions for some programs, but not for educational programming. In February 2025, 1,432 inmates on the ABE program waitlist were assessed to have a “probable” or “highly probable” need for educational or vocational programs to reduce their risk of reoffending. At the same time, many of those who were enrolled were assessed as “unlikely” to need educational programming to reduce their risk of reoffending (43 percent, or 1,134 inmates). During the same period, 1,046 inmates enrolled in a CTE program (70 percent) had been assessed as having an “unlikely” need for education or vocational training, while 1,308 inmates on CTE waitlists were identified as having a “highly probable” or “probable” need for it. Forty-five percent of the 1,219 inmates who were released in 2024 and who were on an ABE and/or CTE waitlist were determined by DOC’s assessments to need educational or vocational programming to reduce their risk of reoffending.

DOC’s educational programming is hindered by staff vacancies, inadequate IT, and use of funding for some non-educational needs

In addition to the correctional officer vacancies mentioned previously, vacancy rates among DOC teachers are high. The vacancy rates among DOC teachers would have placed DOC in the top 10 vacancy rates in the state among school divisions (2024–25 school year). DOC estimates that it would need an additional $4.3 million to fully fund all 28 vacant instructional positions. JLARC staff estimated that filling these vacancies would allow between 700 and 1,100 additional inmates to enroll in an educational program.

DOC’s educational programs rely on functioning computers and networks for critical tasks like student assessments and instruction. However, only 28 percent of surveyed teachers and principals agreed that internet access at their facility was adequate to support instructional needs; less than half (42 percent) reported that “student-use” computers functioned reliably most of the time; and only 38 percent agreed that IT support and repairs were provided in a timely manner.

At least some of the roughly $37 million in funding appropriated for correctional education is being used by DOC for non-instructional purposes. According to DOC central office staff, some teachers are being paid overtime to work certain security posts outside of regular hours. This practice may be warranted at some facilities, especially when there are critical security staffing shortages, but educational program funds should not be used to cover these overtime costs. JLARC staff estimate that as much as $220,000 appropriated to DOC for educational purposes in FY25 was used to pay staff overtime at DOC facilities, some of which may have been for security purposes. While less than 1 percent of the program’s appropriations, this funding could have instead been invested in low-cost program improvements, like professional development, which many DOC teachers expressed a desire for.

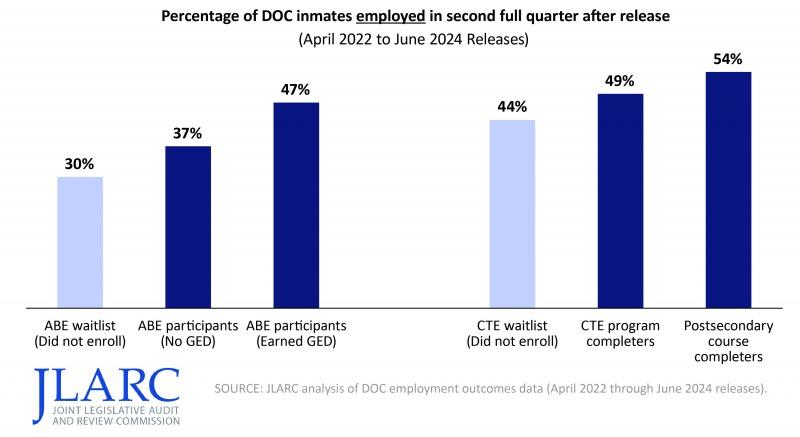

DOC should ensure that its ABE program appropriately balances GED attainment and functional literacy

In recent years, DOC has placed a greater emphasis on GED attainment and revised its testing eligibility policies and funding to support increased attainment. These efforts contributed to a fourfold increase in the number of GEDs attained by DOC inmates (from 117 in 2022 to 544 in 2024), and an even greater rise in the number of GED subject tests administered, which peaked at nearly 4,300 in 2024.

Although GED attainment has increased, declining pass rates and concerns from DOC central office staff, principals, and teachers indicate that a substantial proportion of students are being tested before they are ready. Subject test pass rates fell from 87 percent in early 2022 to 52 percent in early 2025. Retakes have also grown, increasing from less than 5 percent of tests administered in 2022 to more than a quarter of all tests in 2024. A 50 percent pass rate suggests students are being tested prematurely, representing an inefficient use of limited ABE program staff and space.

DOC’s GED subject test pass rates are declining, indicating a greater proportion of students may be taking tests before they are ready

DOC facility and central office staff also raised concerns that the recent focus on GED attainment has diverted attention away from students at lower academic levels, who comprise most ABE-eligible inmates and who are statistically more likely to reoffend. Available data indicates that academic progress in the ABE program has declined by a small amount in recent years.

Most DOC CTE programs focus on in-demand jobs and skills, but only half of CTE participants are employed two quarters after release

DOC’s CTE programs generally target high-demand occupations or those with many job openings. However, while CTE completers had better outcomes than inmates who remained on waitlists, many did not find or maintain employment within the first year of release, a critical factor for successful reentry into the community. Among inmates who recently completed DOC CTE programs:

- 49 percent were not employed in the first quarter after release, and

- 67 percent did not maintain employment for all four quarters after release.

DOC’s re-entry division provides some employment assistance and has staff at some facilities to help with job skills like interviewing. However, this support is not available at all facilities or to all inmates who will soon be released. In addition, the support is not targeted to specific CTE programs or industries.

In addition, about half of inmates who begin a CTE program do not complete it before they are released. Most inmates who were in a CTE program when they were transferred did not re-enroll in any CTE programs. Education and facility staff can request “transfer holds” when aware of upcoming transfers for program participants, but requests and approvals are inconsistent across facilities.

To expand postsecondary programming, DOC’s central office would need to be more involved in program oversight and development

As of September 2025, 17 of DOC’s 37 major facilities provided postsecondary education through partnerships with higher education institutions (eight community colleges and one four-year university), a recent expansion prompted by the 2020 restoration of Pell Grant eligibility. In February 2025, 2 percent of DOC’s inmates were enrolled in a postsecondary course.

Because of the small amount of programming currently available at correctional facilities, DOC has provided minimal oversight to postsecondary programming at DOC facilities. However, the 2025 General Assembly passed legislation (that was vetoed by the governor in anticipation of this study), which would have significantly expanded postsecondary programming in state prisons. If the General Assembly still wishes to expand postsecondary programming, a more robust central office role is needed.

Most commonly offered associate degree program is likely not most useful for most inmates

The most common DOC postsecondary program offered (as of September 2025)—the Associate in General Studies—does not align with market needs and is likely not the most useful credential for most inmates. This program is designed to provide credits that can be applied toward a bachelor’s degree, including courses such as College Success Skills and Religions of the World.

National experts and correctional staff from other states recommend that postsecondary correctional education programs prioritize teaching skills that enhance an inmate’s employability. While the Associate in General Studies program may be useful to traditional college students, most inmates cannot pursue a bachelor’s degree while incarcerated. Other credentials that could be offered by higher education institutions may better align with the post-release realities for most inmates. Some states, like Ohio, North Carolina, and Washington, have already adopted this workforce-focused approach.

Most jails reported meeting demand for adult education programs, but not CTE; shorter incarcerations make program expansion difficult

While state law permits but does not require educational and vocational programming in local and regional jails, most jails in Virginia report offering some form of adult education (e.g., education, GED testing and preparation, special education). Some jails offer this programming through self-guided adult education courses on tablets or computers.

Fewer jails offer CTE or postsecondary courses. Twenty-eight of the 51 jails responding to JLARC requests reported offering CTE programs, mostly short courses that teach specific credentials or stackable skills. Eleven facilities offer postsecondary, credit-bearing courses for inmates through partnerships with community colleges.

Most jails reported being able to meet demand for adult education programs, but not for CTE and postsecondary education programs. The most common reasons given were constraints on funding, instructional staff, and physical space. Even if the state allocated more resources, providing comprehensive educational programming in jails is difficult because of inmates’ relatively short stays. Pre-trial inmates have frequent court proceedings, and post-trial inmates stay in jail only an average of two months.

Additionally, jail superintendents and sheriffs reported that many inmates have urgent mental health needs that must be addressed before inmates can actively participate in education or other types of jail programming. In 2024, 37 percent of jail inmates were assessed to have a mental illness, a proportion that has been growing in recent years.

If additional educational opportunities in jails are expanded, they should include self-guided pacing courses through tablets, short-term CTE programs, and adult basic education and CTE programs instead of postsecondary courses.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Appropriate funding for additional positions to prepare CTE program participants to find employment once released from DOC custody.

Executive action

- DOC should require that principals consider inmates’ assessed need for educational and vocational programming to reduce their risk of recidivism when making program enrollment decisions.

- DOC should take steps to ensure that all funds appropriated for educational programming are used only to support such programs.

- DOC should better assess student readiness to take the GED test, monitor GED score reports to identify skill gaps, and modify programming to address these gaps.

- DOC should focus more on improving lower-functioning inmates’ foundational literacy skills and grade progression and less on the frequent administration of GED tests in its adult education program.

- DOC should require that correctional facilities regularly report to the DOC director on all inmates’ education gains, not just GED attainments.

- DOC should develop clear criteria for using temporary transfer holds for inmates who are in CTE programs and require staff to use these criteria to guide their CTE participant transfer decisions.

- DOC should elevate the position of the college coordinator at its central office to report directly to DOC’s superintendent of education.

- DOC should evaluate whether a different postsecondary program than the Associate in General Studies degree would be more useful to inmates after release and, if so, take steps to offer it in its place.

The full list of recommendations is available here.