Virginia's Self-Sufficiency Programs and the Availability and Affordability of Child Care

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2022, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission directed staff to review the effectiveness of Virginia’s programs for helping poor Virginians improve their employment and wages and make progress toward self-sufficiency. Staff were also directed to examine the availability and affordability of child care, which is a well-documented barrier to achieving self-sufficiency.

ABOUT VIRGINIA'S SELF-SUFFICIENCY PROGRAMS

This study focuses on Virginia’s TANF, SNAP, and Child Care Subsidy Program, as they are the only three programs with requirements designed to improve participants’ employment and earnings or that require participants to engage in work activities to receive benefits. TANF and SNAP are administered at the state level by the Virginia Department of Social Services and, locally, by local departments of social services. The Child Care Subsidy Program is administered by the Virginia Department of Education and local departments of social services. In FY23, $3.5 billion in state and federal funds were spent on these three programs.

WHAT WE FOUND

Few Virginians in poverty qualify for self-sufficiency programs, and those who do rarely exit poverty or achieve self-sufficiency

Approximately 856,000 Virginia households live either in poverty or below a standard of living that allows them to afford their basic living expenses (i.e. “self-sufficiency”). However, only about 1 percent of these households participate in the programs designed to help Virginians become self-sufficient. In FY22, only 9,900 households participated in the primary program intended to move impoverished Virginians toward self-sufficiency, Virginia Initiative for Education and Work (VIEW), in which most adult TANF recipients are required to participate. The other program, SNAP Employment and Training (SNAP E&T), is offered at only 37 of the state’s 120 local departments of social services and served about 1,160 households per month in 2022.

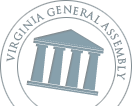

JLARC’s analysis of a cohort of approximately 265,000 2018 TANF-VIEW, SNAP, and SNAP E&T participants confirmed results of other national and Virginia-specific analyses that self-sufficiency programs have limited impact on participants’ employment and wages. Employment rates for these VIEW and SNAP E&T participants did not increase over time, and while half experienced wage increases by 2022, the median wage for the group remained below the federal poverty threshold. By 2022, very few participants earned wages that would allow them to be self-sufficient (2 percent of TANF-VIEW clients and 7 percent of SNAP E&T clients).

Few self-sufficiency program clients earned self-sufficient wages by 2022

Few TANF and SNAP clients participate in workforce development programs

TANF-VIEW and SNAP E&T recipients would benefit from either employment or training services to improve their employability and earning potential, and they likely would benefit from services and programs offered by the state’s workforce development system. However, fewer than 2 percent of TANF and SNAP recipients enrolled in the state’s workforce development system each year from 2018 to 2022. While those who did participate experienced increased wages, their outcomes were less positive than those of all other workforce program participants during this period.

Only some local departments of social services (“local departments”) have formal agreements with local workforce development boards to coordinate the provision of workforce services between them, even though workforce programs are able to provide more intensive job training services than local departments, and state law requires these agreements. There is widespread lack of understanding among VIEW and SNAP E&T case workers about the services available through workforce development programs, which is perpetuated by infrequent arrangements to locate VIEW, SNAP E&T, and workforce development case workers in each other’s offices, even though state-level staff have indicated that such co-location is ideal.

VIEW policies encourage activities that will lead to relatively low-paying, dead-end, unstable jobs

VIEW clients are often assigned and encouraged to participate in low-effort activities that do not help clients gain additional skills and qualifications needed for jobs that may lead to self-sufficient wages. In general, VIEW clients are not encouraged to pursue employment with advancement opportunities. Virginia’s VIEW policy dictates that clients who are not already working full time should be assigned job search as their first VIEW activity. Clients assigned to job search are required to make job contacts and must accept an offer of full-time employment that pays at least minimum wage. This policy encourages clients to quickly obtain employment, regardless of the quality or wage potential of the job. While obtaining any full-time job may be an improvement to the clients’ immediate economic situation, these jobs generally do not lead to self-sufficiency in the long term. Most of the VIEW clients examined by JLARC staff became employed in industries and jobs with low wages. The majority of these clients did not work full time (40 hours per week), did not work consistently, or did not make at least the minimum wage.

High caseloads, staffing challenges, and inconsistent use of available TANF funding by local departments contribute to poor outcomes

Clients need robust case management to benefit from self-sufficiency programs. Casework, including adequately assessing a client and planning their services and activities, takes time. State law and federal regulations require that clients receive intensive case management throughout their participation in self-sufficiency programs, but local department staff reported being unable to meet this standard because of high caseloads. The median number of VIEW clients per worker was 32 as of August 2023; however, some workers’ VIEW caseloads were as large as 169 clients. Many VIEW and SNAP E&T workers reported carrying caseloads for other benefit programs, such as SNAP or Medicaid, increasing the median total number of clients per worker to 77. There are no caseload guidelines or targets.

Virginia’s self-sufficiency programs offer supportive services intended to help address clients’ barriers to participating in program activities and finding a job. The most common barriers Virginia self-sufficiency clients face are finding child care and transportation. However, many local departments do not fully exhaust their annual funding allocations for VIEW and could spend more of their allocation on supportive services. In FY19 (the last year of data not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic), 24 percent of VIEW clients were in localities whose local departments underspent their funding allocations.

Virginia’s lack of affordable child care services is a major barrier to self-sufficiency

Research literature indicates that without child care, parents may have to reduce their work hours, take lower-level or lower-paying jobs, or drop out of the labor force altogether. This reduces their household income, which can inhibit their ability to achieve or maintain self-sufficiency.

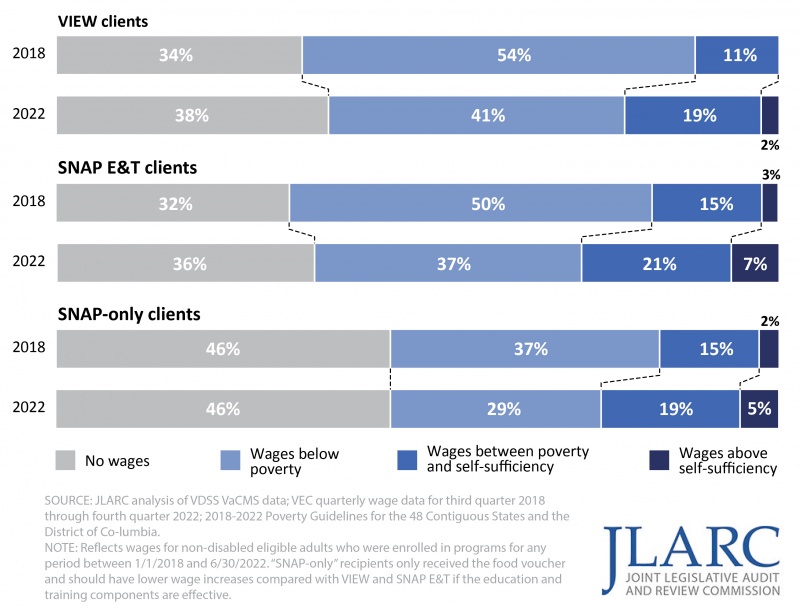

Full-time formal child care in Virginia costs between $100 and $440 per week, per child, on average. Many child care providers charge fees on top of base tuition rates, which further increase the cost of child care. In all regions of the state, for most types of child care and for both one-adult and two-adult households, child care costs surpass 10 percent of the median income. This exceeds what the federal government has deemed affordable, which is child care costs accounting for 7 percent or less of household income. The costs of infant and toddler care exceed 7 percent of household income for more than 80 percent of Virginia families, and the cost of preschool exceeds 7 percent of household income for 74 percent of Virginia families.

Child care is unaffordable for many Virginia households, most notably those with young children

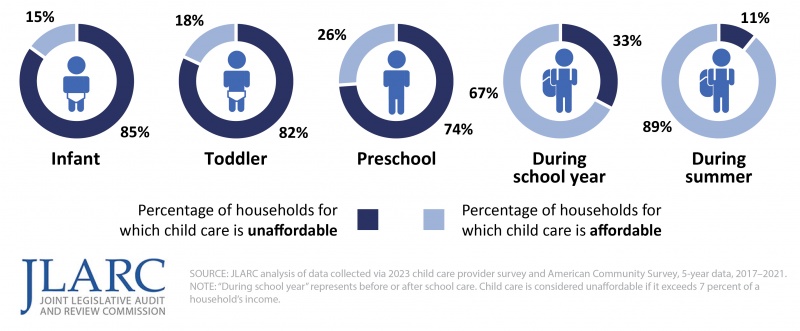

In addition to the high cost of child care, in almost all regions of the state there are not enough child care “slots” to meet demand. Approximately 1.13 million children in Virginia are age 12 and younger and estimated to need child care. About 55 percent (630,000) of these children are school age and only need child care coverage during the parts of the day and year when they are not in school. The remaining 45 percent (500,000) are infants, toddlers, and preschoolers who need full-day, year-round care. Of the Virginia children estimated to need child care, an estimated 990,000 have access to either formal or informal child care. This leaves a statewide shortage of at least 140,000 slots. Child care slots for infants and toddlers are especially needed with a shortage of at least 33,000 slots in the state. Most regions of the state need 3,000 or more infant-toddler slots to meet demand.

The estimate of 140,000 needed slots likely underestimates demand, because it does not take into account operational constraints that reduce the number of actual slots available. Furthermore, many of these slots would likely need to be offered at a reduced rate to be affordable for families with modest incomes.

State regulations can influence the cost and availability of child care, especially through staffing ratios. However, Virginia’s child care regulations, including the staffing requirements, generally align with other states and best practices. Most providers reported that, in their opinion, the regulations are appropriate for maintaining children’s health and safety and that the required staffing ratios create manageable working conditions.

Child care subsidy improves affordability, but expansions are set to expire and encouraging provider participation is challenging

Virginia’s Child Care Subsidy Program is intended to help parents afford child care, enabling them to work, look for employment, or participate in an education or training program. The program uses federal and state funds to reimburse providers for the care they provide to children from low-income families, including TANF and SNAP E&T participants. On average, families participating in the subsidy program spend $860 a year, or 2 percent of their income, on child care—significantly less than the cost of child care for private-paying families and far below the federal government’s affordability threshold of 7 percent.

The 2022 Appropriation Act authorized the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) to fund expansions to the Child Care Subsidy Program using federal COVID-19 relief funding, which is set to expire in FY24. Fifty percent more children received subsidized child care at the end of FY23 than in FY22, and families’ copayments were reduced, further improving their ability to afford child care.

Even with expansion of the program, there are not enough subsidy slots to meet demand, and it can be very challenging—sometimes impossible—for eligible families to find a vendor who either accepts the child care subsidy or has available subsidy slots. Fewer than half (42 percent) of the state’s licensed child care providers are subsidy vendors, and an even smaller (but unknown) proportion of the state’s child care slots can be used by subsidy clients.

One factor that is exacerbating the shortage of subsidy slots is that individuals who are searching for a job are eligible for the child care subsidy, and the program allows these individuals to take up a subsidy slot indefinitely. Some local department staff believe the absence of a time limit has resulted in some parents saying they are looking for work but not doing so in earnest (or at all), which reduces slots available for parents working or participating in a training or education program.

Child care providers choose not to be subsidy vendors for several reasons, but the most common is that they have sufficient enrollment from private-paying families. Other common reasons for not participating in the subsidy program include feeling that the reimbursement process or the additional administrative responsibilities are too burdensome or time consuming. Specifically, the current provider reimbursement process is unnecessarily burdensome. Reimbursement is based on attendance and requires providers to use a cumbersome and unreliable system to collect attendance information.

Unless intervening action is taken, program parameters and funding will return to pre-pandemic levels at the start of FY25, reducing the number of families that receive subsidized child care and reducing its affordability. The Commission on Early Childhood Care and Education is considering how the subsidy program has been affected by recent changes and funding and should be making recommendations for financing the child care subsidy program beyond FY24.

State has limited options beyond the subsidy program to improve child care access

Maintaining recent expansions to the Child Care Subsidy Program is the state’s best opportunity to improve access for families that are most likely to not work because of child care. Still, families with higher incomes cannot qualify for subsidized care, and the lack of child care slots and their costs impacts these families too. Virginia has already implemented nearly all of the approaches most commonly used in other states to improve the availability and affordability of child care. These include: initiatives to incentivize staff and providers to enter and stay in the child care market; training and professional development for child care staff; scholarships for prospective and existing child care staff; retention bonuses; and tax incentives.

The state could consider implementing some other initiatives, such as providing grants or seed funding to open new child care programs and creating a substitute teacher pool. Other states have used these initiatives to improve child care access. Still, child care largely operates in the private market, which limits the state’s ability to significantly influence the inventory or cost of child care.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Require each local department of social services to develop a formal agreement with the local workforce development board in its region concerning coordinated provision of workforce development services to VIEW and SNAP E&T clients.

- Dedicate a portion of federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act funds to facilitate the co-location of Virginia Career Works center staff at local departments of social services on a part-time basis.

- Establish and fund a pilot program for testing an alternative assessment and planning process for a subset of VIEW clients that uses an interdisciplinary team of program and service providers, similar to Family Assessment and Planning Teams for the Children’s Services Act.

- Establish and fund a pilot program to test the impact of financial incentives for self-sufficiency program clients who participate in education and training programs.

- Direct VDSS to pursue participation in an outcome-based performance measures pilot program authorized under the federal Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which could allow Virginia to refocus VIEW on clients’ potential long-term employability and earning potential rather than quick job attachment.

- Require VDOE to issue payments to Child Care Subsidy Program providers based on enrollment, rather than attendance, to reduce providers’ administrative burden.

- Limit to 90 days per job loss occurrence the amount of time families can receive assistance through the Child Care Subsidy Program while they are searching for work on a full-time basis to ensure that the limited slots are as available as possible to already-employed parents.

Executive action

- Virginia Board of Workforce Development rewrite policy to comply with Code of Virginia requirement that each local workforce development board enter into formal agreements with each local department of social services regarding the delivery of workforce services for TANF and SNAP clients.

- Secretary of labor, secretary of health and human resources, and leadership of the Virginia Department of Workforce Development and Advancement (VDWDA) and VDSS evaluate whether administering all or some aspects of VIEW and SNAP E&T through VDWDA and the Virginia Career Works centers would be beneficial.

- VDSS develop modern caseload targets for benefits programs.

- VDSS revise TANF-VIEW and SNAP E&T policies to encourage local departments to use program funds to help clients pay for child care costs that cannot be funded through the state’s Child Care Subsidy Program.

- VDSS monitor local departments’ expenditures of TANF funding allocations and work to ensure that local departments fully spend available VIEW allocations on workforce and supportive services for VIEW clients.

- VDOE and VDSS develop and implement a process to reimburse Child Care Subsidy Program providers based on enrollment rather than attendance by January 1, 2024.

The complete list of recommendations is available here.