CSB Behavioral Health Services

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In December 2021, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) directed staff to conduct a review of Virginia’s community services boards (CSBs). JLARC staff were directed to review CSB behavioral health funding, staffing, and outcomes as well as CSB services for individuals experiencing behavioral health emergencies. Staff were also directed to review the structure of the CSB system to identify any possible opportunities to strengthen the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery.

ABOUT CSBs

Virginia’s CSB system is the state’s primary approach to providing publicly funded behavioral health services in local communities. These services include mental health and substance abuse services. CSBs provide both emergency and non-emergency behavioral health services to individuals. They are designated as the “single point of entry” into Virginia’s publicly funded system of behavioral health services. State law requires every city or county to establish or join a community services board. Virginia currently has 40 CSBs, each serving between one and 10 localities. Across the 40 boards, behavioral health services are delivered at over 500 offices, with each CSB operating between two and 34 service locations.

WHAT WE FOUND

Fundamental restructuring of CSB system is not needed

CSBs face numerous challenges to providing behavioral health services to their communities, including staff shortages, a growing demand for more intensive services, and an increasing administrative workload, which detracts from direct consumer care. Despite these challenges, it was clear in conducting the research for this study that CSB leaders and their staff are highly committed to effectively serving Virginians and fulfilling their role as the primary provider of behavioral health services to individuals with the most significant and urgent behavioral health needs. There is no compelling evidence that adopting an entirely different structure for community-based behavioral health service delivery would result in an inherently more efficient and effective system for Virginia; nor is there evidence that another structure is fundamentally superior to Virginia’s. However, improvements should be made in the current CSB system to ensure that it functions as efficiently and effectively as possible and that CSBs are held accountable for their performance. These changes would not hinder implementation of executive branch officials’ vision for the delivery and funding of behavioral health care in Virginia, but would instead better enable future system improvements.

CSBs are serving an increasing number of Virginians with serious mental illness

In Virginia and nationally, the number of individuals with a mental illness is increasing, particularly serious mental illness. CSBs’ priority consumers for mental health services are those with a serious mental illness, and CSBs served 20 percent more consumers with a serious mental illness in FY22 than compared with a decade ago. Meeting the needs of consumers with a serious mental illness requires CSBs to provide more services per individual and more intensive services. CSBs play a larger role in the provision of services to individuals with a serious mental illness in rural areas where there are often fewer private providers of mental health services.

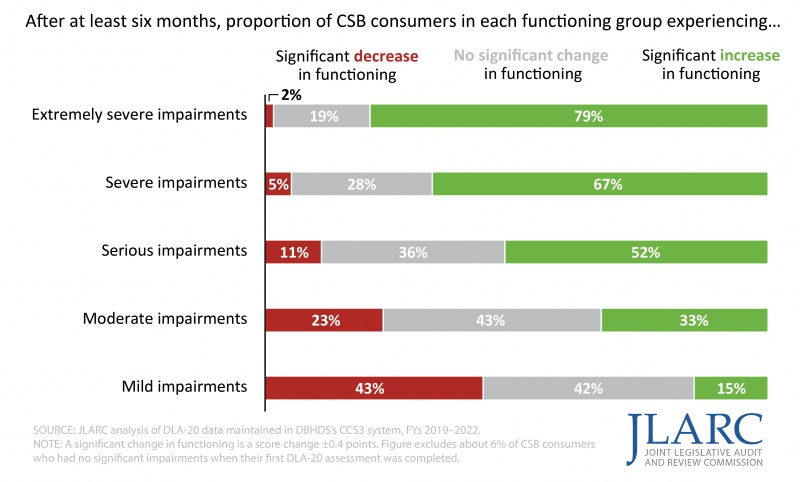

Virginians with significant impairments due to mental illness tend to improve their functioning while receiving CSB services

The majority of CSB consumers who are severely affected by their mental illness generally experienced significant improvements after receiving CSB services. These consumers are the most likely to require inpatient psychiatric hospitalization if they do not receive adequate treatment and are the priority population for CSB services.

Forty-one percent of consumers experienced declines in functioning while receiving CSB services. These consumers typically had higher levels of functioning when they began receiving CSB services despite their mental illness. The reasons for their declines in functioning are unknown, but the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS) should examine why these declines are happening and what improvements to CSB services could be made to help these consumers.

Majority of CSB consumers with most impaired functioning improved while receiving CSB services (FY19–FY22)

CSBs struggle to hire and retain staff, especially for emergency and crisis services, and turnover among CSB staff is high and increasing

CSBs need sufficient numbers of qualified staff to provide timely and effective behavioral health services, to meet state requirements, and to implement statewide initiatives like STEP-VA and the development of the crisis services continuum. However, most of the 40 CSB directors reported having experienced difficulty hiring and retaining qualified staff to deliver behavioral health services over the past 12 months. Directors experienced the greatest challenges hiring and retaining emergency services staff, followed by crisis services staff. Both of these types of staff deliver core CSB services. One-third of surveyed emergency services staff reported that they are considering leaving their jobs in the next 12 months. In addition, the average turnover rate among the 23 CSBs for which data was available increased from 15 percent in FY13 to nearly 27 percent in FY22, and vacancy rates average more than 20 percent among direct care staff.

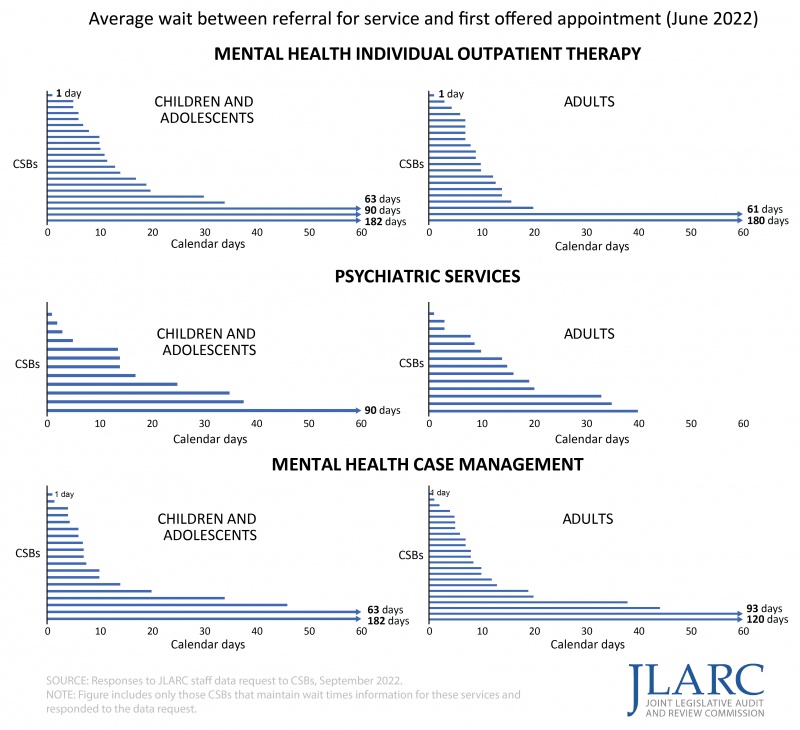

Staffing challenges are affecting consumers, key CSB partners, and state initiatives. Staffing shortages are contributing to long wait times for behavioral health services at some CSBs. Self-reported data from the CSBs indicates particularly long waits for psychiatric services and mental health outpatient therapy, especially for children and adolescents, and outpatient therapy for substance use disorders. In addition, because of CSBs’ staffing challenges, only four of the 40 CSBs reported typically being able to conduct “same day assessments” for all consumers on the same day they are sought. Nine CSBs reported that they were typically able to conduct same day assessments for only half or fewer of the consumers who sought one.

Some CSBs reported particularly long waits for mental health outpatient therapy and psychiatric services, especially for children and adolescents (Consumers referred to services in June 2022)

Compensation and administrative burdens are key reasons CSBs are having trouble recruiting and maintaining staff. CSBs must increasingly compete with the private sector for behavioral health staff, and data shows that comparable jobs at other behavioral health establishments pay higher salaries and require less administrative work. Licensed clinical social workers and licensed professional counselors at a majority of CSBs are paid salaries at least 10 percent less than the same types of professionals working for other behavioral health employers in Virginia, according to March 2022 data. Most CSB executive directors reported that compensation was one of the top three factors that made it difficult for their CSB to recruit and hire qualified staff for behavioral health services. The most commonly reported reason that CSB directors gave for staff turnover was “burdensome administrative requirements,” and CSB staff most commonly recommended reducing administrative burdens on direct care staff as a solution to staffing challenges. CSB direct care staff generally report spending (1) less time with patients and (2) more time on administrative tasks than the same types of professionals working for other behavioral health employers in Virginia.

CSBs recommend state hospital admissions for some individuals who do not need that level or type of care and do not consistently fulfill their discharge planning responsibilities

State psychiatric hospital admissions increased 68 percent between FY12 and FY21, and state hospitals have been operating at or near capacity with waitlists. An increase in civil temporary detention order (TDO) admissions to state psychiatric hospitals has been a major factor contributing to the increase in state hospital admissions. CSB emergency services staff, called “preadmission screening clinicians,” are responsible for determining whether an individual—who has been placed under an emergency custody order by a magistrate or law enforcement officer—meets the criteria to be placed under a TDO. These CSB staff are also responsible for finding a placement for the person to receive treatment while under a TDO.

Some of the pressure on state hospitals’ capacity may be relieved by providing CSBs with better and more frequent training to ensure that they make appropriate TDO and state hospital placement recommendations. Wide variation in TDO rates across CSBs indicates inconsistencies in preadmission screening practices and recommendations. In FY21, the proportion of CSB evaluations that resulted in a TDO ranged from 11 to 71 percent across CSBs. Additionally, state hospital staff indicated that many individuals under TDOs who were admitted to their facilities did not require the level or type of care provided there. CSB preadmission screening clinicians reported that some adults and children they have recommended be placed in a psychiatric hospital could have been better served in an alternative setting if one were available.

CSBs could also help reduce pressure on state psychiatric hospital capacity by improving their efforts to safely discharge state hospital patients. Not all CSBs are consistently creating quality discharge plans for state hospital patients or doing so in a timely manner. In April 2022, 10 percent of individuals in psychiatric hospitals who had been waiting more than seven days for their discharge were waiting on a CSB to finish certain tasks. At that time, these individuals had remained in the hospital an average of 79 days after they were determined to be eligible for discharge.

State’s psychiatric bed registry wastes limited time and staff resources

CSB staff need to be able to locate a TDO placement for individuals efficiently, because they have limited time to identify the most appropriate placement. If an appropriate placement cannot be found in a timely manner and no state psychiatric hospital beds are available (sidebar), the individual may either be released from custody without being placed under a TDO or spend their TDO in a hospital emergency room. In either scenario, the individual may not receive the behavioral health services they need.

The state’s psychiatric bed registry is intended to make CSBs’ search for a psychiatric hospital bed efficient, but it lacks real-time, useful information about the psychiatric beds available. Ninety-two percent of surveyed CSB staff with bed search responsibilities indicated that the bed registry was either not at all useful or not being used as part of their bed search process. A JLARC staff review of the DBHDS bed registry in June 2022 showed that 13 of the 25 facilities listed had not updated their availability in at least two days, and some had not updated their availability in months.

Expanding residential crisis stabilization units would help reduce inappropriate psychiatric hospital placements and help with patient discharge

Residential crisis stabilization units (RCSUs) are a type of treatment facility, usually managed and staffed by CSBs, where individuals in crisis may stay temporarily to receive behavioral health services to help stabilize their condition. CSB executive directors and preadmission screening clinicians reported that additional RCSU beds would help avoid the need to place some individuals in state psychiatric hospitals. RCSUs would more directly help alleviate state psychiatric hospital admission pressures than other types of crisis services, such as mobile crisis services and 23-hour crisis stabilization services, because they can be equipped to treat individuals under a TDO. They can also provide an appropriate placement for individuals who are released from a state psychiatric hospital but who need additional residential treatment.

There are only three RCSUs for children and adolescents in Virginia, which operate only 25 beds in total. Additionally, not all licensed beds for adults are staffed because of CSBs’ current recruitment and retention challenges, and a large portion of Southside Virginia’s population does not have an adult RCSU within a one-hour drive. CSBs that serve these areas have state psychiatric hospital admission rates significantly higher than the statewide rate. Additional state resources could be devoted to fully staffing the state’s existing RCSUs and to developing additional RCSUs, particularly for children and adolescents and in underserved areas of the state.

CSBs’ Medicaid funding has declined; some CSBs are not consistently billing Medicaid or receiving reimbursements from MCOs

Total behavioral health funding for the CSB system increased from $941 million to $1.09 billion (16 percent) adjusted for inflation, between FY12 and FY22, and additional non-Medicaid state general funds and local funding drove most of this growth. In contrast, even though the proportion of CSB consumers covered by Medicaid has increased, Medicaid funding for CSB behavioral health services has decreased 15 percent over the past decade. A majority of CSBs received less Medicaid funding in FY22 than in FY12. This trend is concerning because Medicaid reimbursements account for about 20 percent of all CSB funding.

Maximizing Medicaid reimbursement helps ensure non-Medicaid state general funds and local funds are used most efficiently, but CSBs are not receiving as much Medicaid funding as they could be. Some CSBs are reportedly not billing Medicaid because of the complexity of billing procedures or requirements for reimbursement, and they are reportedly using state general funds to cover costs of serving Medicaid enrollees. CSBs are also reportedly not receiving timely and accurate Medicaid payments.

CSBs attribute billing and reimbursement issues to the increased complexity of the claiming and billing process associated with integrating behavioral health services into Medicaid managed care contracts (MCOs), which requires more staff time and makes it difficult to collect Medicaid reimbursements in a timely manner. Commonly reported concerns include duplicative training requirements; delays in approving providers to bill for services; differences in authorization and billing processes and requirements across MCOs; frequent changes to MCO billing systems; and increased rates of reimbursement denials by MCOs.

State does not adequately oversee performance of CSBs

JLARC reports, legislative commissions, and studies from subject-matter experts have concluded that Virginia’s CSB system has not been held accountable for delivering high quality services that produce positive outcomes for consumers. Three key deficiencies prevent adequate state oversight of CSBs: the lack of an explicit, overarching purpose and goals that establish guiding expectations for the system; inadequate data systems to document and evaluate CSB consumers’ outcomes and CSB operations; and insufficient state resources dedicated to overseeing, evaluating, and improving CSB performance. There has been a lack of state direction or guidance to CSBs regarding the performance of their behavioral health service responsibilities and no meaningful effort to ensure that their responsibilities are fulfilled.

DBHDS should devote more attention to designing effective performance measures for key CSB responsibilities and collecting relevant performance information from CSBs. This improved insight will allow the agency, other executive branch stakeholders, the General Assembly, and local governments that establish and help fund the CSBs to better understand how CSBs are performing and what steps can be taken to improve performance. DBHDS has no formal processes or data to understand critical aspects of CSBs’ service delivery and consumer outcomes, such as preadmission screening or discharge planning. No DBHDS staff have been dedicated to monitoring the quality of behavioral health services at CSBs. The performance contracts themselves are insufficient to allow the state to assess CSB performance, provide targeted technical assistance, or hold CSBs’ accountable for fulfilling their behavioral health services responsibilities. State law provides DBHDS with mechanisms to hold CSBs accountable for meeting performance expectations, but, in practice, DBHDS rarely uses them. This is at least partially because the agency lacks good information on CSB performance.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Require DBHDS to report annually to the State Board of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services and the Behavioral Health Commission on CSBs’ performance in improving the functioning of consumers receiving behavioral health services.

- Appropriate funding for salary increases for all CSB direct care staff.

- Direct DBHDS to eliminate documenting and reporting requirements for CSBs that are not essential to ensuring that CSB consumers receive effective and timely services.

- Direct DBHDS to review a sample of CSB preadmission screenings for quality on an ongoing basis and to contract with higher education institutions to deliver training on preadmission screening and provide technical assistance to CSB staff.

- Repeal the requirement in §37.2-308.1 of the Code of Virginia that every state facility, community services board, behavioral health authority, and private inpatient provider licensed by DBHDS participate in the acute psychiatric bed registry.

- Appropriate funding to support the development and operations of additional residential crisis stabilization facilities in underserved areas of the state and for children and youth.

- Direct DBHDS and DMAS to ensure that CSBs are billing for all Medicaid-eligible CSB services.

- Amend the Code of Virginia to clearly articulate the purpose of CSB behavioral health services and require DBHDS to develop clear goals and objectives for CSBs that align with and advance those purposes and include them in CSBs’ performance contracts.

- Direct DMAS to work with the six Medicaid MCOs to adopt standard requirements and procedures for billing and reimbursement.

- Direct DBHDS to develop clear and comprehensive requirements and processes for monitoring CSBs’ performance and to report CSB-level performance information to each local CSB governing board, the Behavioral Health Commission, and the State Board of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services.

- Direct DBHDS to regularly monitor CSB compliance in meeting performance contract requirements and use available enforcement mechanisms, as necessary, to ensure CSB are in substantial compliance with these requirements.

Executive action

- DBHDS to contract as soon as practicable with a vendor to implement a secure online portal for CSBs to upload and share patient documents with inpatient psychiatric facilities to help find an inpatient placement for consumers who are under a TDO.

- DBHDS to oversee CSBs’ discharge planning efforts and develop mechanisms for corrective action, technical assistance, and guidance to use with noncompliant or underperforming CSBs.

- DBHDS to complete a comprehensive review of all CSB performance contracts and revise all performance measures to include measurable goals, benchmarks, and specific monitoring activities to hold CSBs accountable for performance.

- DBHDS to provide status updates on its initiative to improve the exchange of consumer and service data between CSBs and DBHDS to the Behavioral Health Commission and the State Board of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services at least every three months until the project is complete.

The complete list of recommendations is available here.