Children's Services Act & Private Special Education Day School Costs

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2019, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) asked staff to conduct a review of the Children’s Services Act (CSA) program. The study resolution required staff to examine drivers of spending growth in the CSA program, the cost effectiveness of services, especially private special education day school, and state and local oversight and administration of CSA.

ABOUT CSA

The CSA program was created in 1992 to more efficiently and effectively serve Virginia children who require services from multiple programs. Services include community-based behavioral health services (e.g. outpatient counseling) for children in foster care or at risk of foster care placement and services delivered to students with disabilities who are placed in private special education day schools instead of public school. In FY19, 15,656 children received services funded by CSA, the majority of whom were in foster care or private special education day school placements.

WHAT WE FOUND

Spending on private special education day school services has driven overall CSA spending growth

CSA spending for private special education day school services (“private day school”) has more than doubled since FY10, growing by approximately 14 percent per year from $81 million to $186 million. In 2019, private day school spending accounted for 44 percent of all CSA spending. If spending trends continue, within the next several years the majority of the CSA program’s expenditures will be for private day school services.

Children placed in private day schools typically have an emotional disturbance, autism, or some other childhood mental disorder, and exhibit behaviors that public schools have difficulty managing.

Half of the growth in private day school spending is explained by increasing enrollment in these schools. Enrollment has grown 50 percent over the past 10 years because of three factors: more new children placed in private day school each year, children being placed in private day school at younger ages, and children spending more time in private day school.

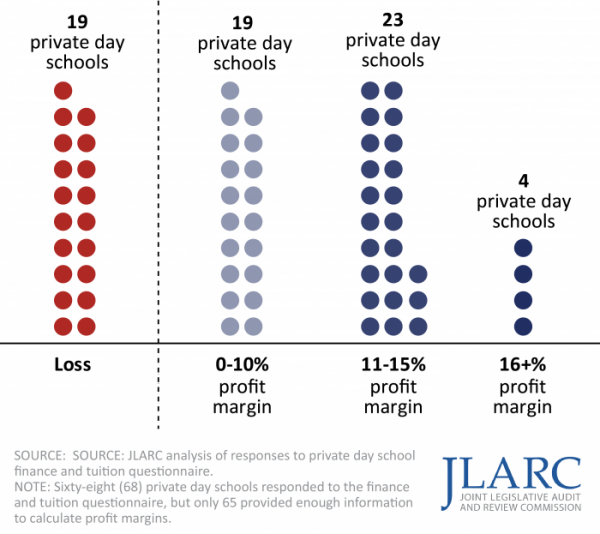

Increasing tuition rates charged by private day schools and greater use of additional services offered by private day schools also contributed to spending increases. Tuition rates increased by 25 percent between FY10 and FY19, or an average of 3 percent annually, similar to inflation growth during that time. Annual tuition rates for private day schools are costly ($22,000 to $97,000 per child), and the lack of insight into tuition rates has raised questions about their reasonableness and the schools’ profits.

However, private day schools appear to charge tuition rates that are consistent with the cost of providing low student-to-staff ratios in small environments, and a majority of schools do not earn excessive profits. On average, private day schools earned a 6 percent net profit in 2019.

Majority of private day schools responding to JLARC questionnaire generated profit levels of 10 percent or less

Restricting use of CSA funds to private day school services could prevent children from receiving comparable services in a less restrictive setting

State law and policy do not permit CSA funds to be spent on public school services. School divisions therefore cannot access these funds to provide services that could keep children in public school or transition them back to public school from a more restrictive placement in a private day school. School divisions do have federal, state, and local funding to pay for services delivered within the public schools, but state and federal funding has declined. At the same time, the number of students receiving special education services and the severity of their needs have been increasing.

Prohibiting CSA money from being spent on services that could help keep students in their public school means that students must be placed outside of their school, in a private day school, to access more intensive services. Private day schools are considered one of the more restrictive placements because they are separate from public schools, and students have little to no access to their non-disabled peers. Virginia places a higher percentage of students with disabilities in more restrictive out-of-school settings than 37 other states, and Virginia’s out-of-school placement rate has increased over the past 10 years.

Some intensive services delivered in private day schools (such as one-on-one aides) could be delivered in the public school just as they are in a private school. Without the restriction on where services have to be delivered for CSA funds to be used, more students could receive needed intensive services within their public schools instead of being placed in a private day school.

VDOE would be a more logical administrator of private special education day school funding

The CSA program currently pays for private day school placements but cannot affect placement decisions or students’ service plans. Consistent with federal law, school district IEP teams make private day school placement decisions, and local CSA programs have no control over these decisions even though they pay for the services. Because the Virginia Department of Education is responsible for administering funding and programs for special education services in Virginia’s school divisions and already licenses private day schools, VDOE would be a more logical and potentially effective administrator of this portion of CSA funding.

Private day school performance expectations should be comparable to those for public schools

Stakeholders and parents of private day school students do not have information on the same basic metrics for private day schools that are reported for every public school in the Commonwealth. Unlike public schools, data has not been consistently published on outcomes for students who attend Virginia’s private day schools. While the private day school accreditation process reviews several aspects of private day schools’ educational quality and school operations, it primarily relies on observations and subjective assessments to make determinations about school quality.

State regulations on the use of restraint and seclusion in private day schools are more permissive than restraint and seclusion regulations in public school. In most cases, students who are placed in private day schools have behaviors that are too severe or challenging for public schools to manage effectively. Students with these behaviors are more likely to be subject to restraint and seclusion behavior management techniques. Despite the need to use these techniques in private day schools, the regulations governing them do not require as much documentation of restraint and seclusion incidents, or as much planning to prevent future incidents.

CSA services benefit majority of children, but the multidisciplinary service planning process can delay the start of services

Case managers reported that a majority of CSA children on their caseloads have shown improvement in the past year and that CSA’s multi-disciplinary service planning approach adds value beyond what they can contribute on their own. An analysis of changes in children’s scores on the program’s standardized assessment instrument supports case managers’ experience. On average, children who receive community-based services funded by CSA, such as outpatient counseling or therapeutic mentoring, show improvements in behavior, school attendance, and emotional issues over time. In particular, children in CSA’s community-based services improved most related to potentially dangerous behaviors like self-harm, running away, and bullying. Notably, children in residential services (11 percent of the CSA population) generally did not show improvement over time, and their behaviors tended to worsen.

While CSA’s services and multidisciplinary approach appear to benefit children, many children experience delays in receiving services. The state requires CSA programs to hold Family Assessment and Planning Team (FAPT) meetings to develop children’s service plans, which must then be approved by a separate group—the Community Policy and Management Team. Localities hold these team meetings with various frequencies. In an estimated one-fifth of local CSA programs, children referred to CSA could wait one month or more to begin services after they are referred to the program.

More children could be served through CSA

CSA requires the state and local CSA programs to serve children in or at risk of being placed in foster care and children with disabilities who require placements in private day schools. The CSA program must cover these “mandated” children at a “sum-sufficient” level, meaning the program must pay for the entire cost of services.

The state also provides funding that local CSA programs can use to pay for services for children with less severe emotional and behavioral issues, but nearly half of Virginia’s localities choose not to. These children are not eligible for sum-sufficient funding from the state, per the criteria set out in the Code of Virginia, and are referred to as “non-mandated” children.

Not serving non-mandated children may exacerbate two problems that the CSA program was designed to address—delayed intervention in at-risk children’s circumstances and geographical disparities in service availability. About 18 percent of Virginia’s children live in localities that do not serve non-mandated youth.

Serving non-mandated children could be an effective preventative strategy, and the General Assembly could consider requiring local programs to use available funding to pay for services for these children, resulting in more than 300 additional children receiving CSA-funded supports. This would also increase state and local CSA costs, but services for these children cost less, on average, than services for children in the “mandated” eligibility category.

CSA program could benefit from more well-defined OCS responsibilities and active OCS role

The CSA program’s locally administered structure allows for necessary flexibility, but some local programs are not operating as intended. CSA is designed to encourage local programs to use a “systems of care” approach to service planning, but some local governments view CSA simply as a state funding source for children’s services. The reluctance of some localities to embrace this philosophy was cited as a concern by numerous stakeholders.

Effective OCS supervision of local programs could help improve local CSA programs’ effectiveness, but the Code of Virginia does not give OCS sufficient responsibility for ensuring that local programs operate effectively. Neither OCS nor any other state entity has clear authority to intervene when a local CSA program is ineffective, only when it is not in compliance.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Allow funds reserved for private special education day school services to be used to pay for special education services and supports delivered in the public school setting, either to prevent children from being placed in more restrictive settings like private day school, or to transition them back to public school from more restrictive settings.

- Transfer funding for private special education day school services from the CSA program to VDOE.

- Direct VDOE to annually collect and publish performance data on private day schools that is similar to or the same as data collected and published for public schools.

- Direct the Board of Education to develop and promulgate new regulations for private day schools on restraint and seclusion that mirror those for public schools.

- Require all local CSA programs to serve all children identified as eligible for CSA funds, including those categorized as “non-mandated.”

- Direct OCS to more actively monitor and work with local CSA programs that need technical assistance or are underperforming.

Executive action

- Require local programs to measure, collect, and report data on timeliness in service provision and target assistance to programs with the greatest timeliness concerns.

The complete list of recommendations and policy options is available here.