Gaming in the Commonwealth

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

The 2019 General Assembly directed JLARC to conduct a review of casino gaming laws in other states, evaluate the Commonwealth’s current and potential gaming governance structures, project potential revenues from expanding legal forms of gaming, and evaluate the impact of expanding gaming on the Virginia Lottery, historical and live horse racing revenue, and charitable gaming revenue. SB 1126 was passed by the 2019 General Assembly to authorize the development of casinos in five localities—Bristol, Danville, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Richmond—and its enactment was made contingent on the JLARC review and approval by the 2020 General Assembly.

ABOUT GAMING IN THE COMMONWEALTH

Gambling has long been prohibited in Virginia, with the exception of lottery, charitable gaming, and wagering on horse races. Virginians currently wager over $1 billion annually on these forms of gaming, generating about $600 million in revenue for various purposes, primarily K–12 education. Nearby states permit more forms of gambling than Virginia does, including casino gaming, sports wagering, and online casino gaming.

WHAT WE FOUND

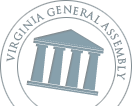

Casinos authorized in SB 1126 are projected to generate about $260 million annually in state gaming taxes and have a positive, but modest economic impact on local economies

Resort-style casinos could be built and sustained in Bristol, Danville, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Richmond, according to estimates from The Innovation Group, a national gaming consultant. These estimates assume an initial $200 million to $300 million capital investment and an annual gaming revenue state tax rate of 27 percent (the national median). Casinos in these five locations are projected to annually generate about $970 million in net gaming revenue and approximately $260 million in gaming tax revenue for the state. (For comparison, the Virginia Lottery generates over $600 million annually after prizes are paid out.)

About one-third of total casino revenue is projected to be generated by out-of-state visitors. Out-of-state visitors would contribute especially to the viability of the Danville and Bristol casinos because of their small local markets; this would also make them vulnerable if casino development were to occur in North Carolina and Tennessee.

Each casino is projected to employ at least 1,000 people, which would have a more meaningful impact in Bristol and Danville because of the relatively small size of their local labor forces. The projected median wage of $33,000 for casino employees would be below the median wage in the five SB 1126 localities. Not all casino jobs would represent a net gain of employment for the localities, and nearly half of the jobs would be low-skill and low-wage. Still, many casino jobs would require higher levels of skill and pay higher wages.

Authorizing a casino in the Northern Virginia market is projected to increase state revenue and economic benefits

A casino in Northern Virginia, which was not authorized in SB 1126 but examined as part of this study, would increase statewide gaming tax revenue by an estimated additional $155 million (59 percent) and employ an additional 3,200 workers. A Northern Virginia casino is projected to attract substantial revenue from out-of-state customers and retain in state about $100 million that Virginia residents are currently spending at casinos in other states.

Five casinos projected to generate approximately $260 million in state gaming tax revenue (2025)

Casino employment as a proportion of labor force for casino localities

Casino employment as a proportion of labor force for casino localities

|

Region |

Labor |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Unemployment rate |

Casino employees |

Casino employees as % of labor force |

|

Bristol |

104,099 |

100,339 |

3,760 |

3.6% |

1,067 |

1.0% |

|

Danville |

50,125 |

48,051 |

2,074 |

4.1 |

1,582 |

3.2 |

|

Norfolk |

464,991 |

450,631 |

14,360 |

3.1 |

1,509 |

0.3 |

|

Portsmouth |

553,100 |

535,529 |

17,571 |

3.2 |

1,384 |

0.3 |

|

Richmond |

540,993 |

524,570 |

16,423 |

3.0% |

2,050 |

0.4% |

SOURCE: The Innovation Group and JLARC staff analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data and U.S. Census Bureau data.

NOTE: Casino employees are employees working directly at casinos; excludes secondary employment because secondary employment is often based in localities outside of the five host localities. Labor force data is 2018 annualized averages, comprising 2018 monthly data. Assumes 27 percent gaming revenue tax rate.

*Labor force for a casino region is defined as all localities from which at least 5 percent of workers in a casino host locality commute on a daily basis. For example, the Bristol region is defined as Sullivan, County TN; Bristol, VA; and Washington County, VA.

Five casinos authorized by SB1126 would be viable under a nationwide median tax rate of 27 percent

The tax rate applied to casino gaming revenue significantly affects the total gaming tax revenue collected by the state. However, higher tax rates can affect casinos’ profitability, and therefore the size and amenities of the casinos. Developers typically size the scale of their casinos to what a market can support, and there is no guarantee that developers will build a larger casino under a lower tax rate. However, casinos in more populous locations can typically remain profitable at a higher tax rate. SB 1126 did not include a tax rate although previous versions of the bill and other similar legislation included tax rates between 10 and 15 percent. TIG found all five SB 1126 casino markets would be able to support “resort-style” casinos at the national median tax rate of 27 percent.

Sports wagering and online gaming are projected to have smaller fiscal and economic impacts

A fully developed sports wagering industry in Virginia could generate up to $55 million in annual gaming tax revenue for the state, depending on how it is structured, and online casino gaming could generate about $84 million each year. Unlike online casino gaming, which would most likely depend on the opening of casinos, sports wagering could be implemented without casinos and could be offered sooner.

Beneficiaries of existing gaming would see proceeds decline, especially historical horse racing

Casino gaming is projected to negatively affect revenue generated by most forms of existing gaming in Virginia, which would in turn decrease the revenue available for the causes they support. The biggest impact would be to revenue generated by historical horse racing (HHR), a small portion of which supports Virginia’s revived live horse racing events. This revenue is projected to decline substantially (45 percent) from what it likely would have been without casino competition, and therefore tax revenue generated by HHR wagering would also decline. Lottery proceeds for Virginia’s K–12 public education are projected to decline slightly ($30 million or 3.6 percent). Charitable gaming proceeds are projected to decline slightly at the statewide level ($3.1 million, or 4 percent), with larger localized impacts to charitable gaming operations located near casinos and the organizations they support.

Expanding gaming in Virginia will increase the number of people at risk of harm from problem gambling

The prevalence of problem gambling in Virginia has not been measured, but evidence from national studies and states with a broad array of gaming options suggests that an estimated 5 to 10 percent of adults may experience gambling problems. While research does not consistently show an increase in the prevalence of problem gambling after the introduction of casinos in a state, more people will at least be at risk of experiencing problems as gambling opportunities increase.

The negative impacts of gambling are not limited to problem gamblers; research consistently shows adverse effects on others, most often a spouse or partner, but also the parents and children of problem gamblers, as well as other family members and close friends. The negative effects of problem gambling can be severe in a small portion of cases, and include financial instability and mental health and relationship problems.

Virginia’s existing problem gambling prevention and treatment efforts are minimal despite the public’s access to gambling through the lottery, historical horse race wagering, charitable gaming, and other avenues. States typically fund problem gambling prevention and treatment programs with gaming tax revenue, which should be considered even if the General Assembly does not authorize additional forms of gaming.

States award licenses for casinos using a competitive selection process and in-depth investigations of key personnel

Most of Virginia’s peer states use a competitive bidding process to award casino licenses, which creates market competition. Market competition helps ensure that the few available casino licenses are awarded to the most qualified and financially stable owners/operators who submit the most realistic and responsible proposals. A competitive selection process is especially important in a limited casino market in which the limited number of casino licenses effectively creates a monopoly for casino owners/operators. A limited casino market is contemplated in SB 1126, but a competitive bidding process is not included in the legislation. Virginia could use a competitive process to maximize the financial and economic value of casino licenses and minimize risks to the state, localities, and the public.

A state’s gaming regulatory board, or a designated selection committee, typically creates specific selection criteria for evaluating casino proposals and issuing an award to the proposal or proposals most qualified to successfully operate a casino. These criteria could include, for example, a specific capital investment threshold, plans to maximize positive local impacts, or plans to prevent and treat problem gambling, among other criteria.

Criteria can also be included to reflect the interests and preferences of state policymakers and host communities. For example, a host community may prefer the use of local assets (such as an existing building), resources (such as the local labor force), or local ownership to maximize local impact and reflect the character of the local community. The General Assembly could also stipulate that special consideration be given to awarding a license to a recognized tribal nation to own or operate a casino. Specifying such preferences in an RFP would be similar to the preferences that are commonly used in the state procurement process for goods and services, such as the preference for veteran-owned businesses.

In addition to vetting casino development proposals through a competitive selection process, states conduct in-depth background and financial investigations of casino executives and key personnel. These investigations ensure that the executives and other personnel who will be operating a state’s casinos have a sound financial history and that they do not have a history of financial or other crimes.

Expanded gaming would be a major new undertaking, even if oversight and administration were assigned to the Virginia Lottery

SB 1126 would assign administration and oversight of casinos and additional forms of gaming to the Virginia Lottery. Regulatory Management Counselors—one of JLARC’s consultants for this study—and other industry experts indicated that a lottery agency can effectively oversee gaming. However, lottery would need to increase staffing by approximately 100 positions; the Virginia Lottery Board’s role and composition would need to change substantially; and lottery would need to expand its longstanding mission of benefiting K–12 education. The state and lottery also would need to mitigate potential conflicts of interest that may arise from the dual responsibility of running a state lottery and regulating the private gaming industry. The state could also consider creating a stand-alone agency to regulate expanded gaming.

Regardless of whether lottery or a stand-alone agency were to oversee and administer expanded gaming, this oversight would be a major new undertaking for the state, costing at least $16 million annually. Lottery’s existing leadership and administrative structure may provide some limited economies of scale (an estimated $2 million annually) for overseeing casino gaming compared to the creation of a new stand-alone agency. However, the majority of lottery staff perform roles specific to lottery and would not offer any economies of scale for overseeing casino gaming.

Expanded gaming would generate positive net revenues for the state, but magnitude depends primarily on the gaming revenue tax rate

Before expenses and reductions to other forms of revenue, total state revenue from the five SB 1126 casinos and additional forms of gaming would range from approximately $154 million to $571 million. Total revenue would depend on the extent to which gaming is implemented and the gaming tax rate applied to individual casinos’ net gaming revenue. After deducting $61 million to $71 million in estimated administrative costs and reductions in HHR generated state taxes and lottery-generated K–12 proceeds, the estimated annual net revenue to the state could range from:

- as low as about $81 million with the five SB 1126 casinos at a low gaming tax rate (12 percent), no other additional forms of gaming, and the highest oversight operational costs; to

- as high as $510 million with a high casino gaming tax rate (40 percent), widespread availability of sports wagering (brick and mortar and mobile options), online casino gaming, and the lowest oversight operational costs.

The more realistic scenario is likely somewhere in between. For example, the state would be projected to see $367 million in positive net revenues using a 27 percent tax rate on the five SB 1126 casinos, revenues from other state and local taxes, broad availability of sports wagering (brick and mortar and online), and online casino gaming. These revenues would be offset by negative impacts from existing forms of gaming and mid-point estimates of administration and oversight costs, including a problem gambling prevention and treatment program.

After expenses, state could collect net positive revenues from expanded gaming ($ millions)

|

Source of revenue/cost |

Estimated annual tax revenue/cost |

|

Casinos |

$262M |

|

Other state taxes from casinos a |

30 |

|

Online gaming |

84 |

|

Sports wagering b |

55 |

|

Total revenue |

$431M |

|

Lottery proceeds to K–12 |

($30) |

|

Gaming agency operations c |

(17) |

|

State taxes from HHR d |

(14) |

|

Problem gambling response |

(4) |

|

Total cost |

($65)M |

|

Net state revenue |

$367M |

SOURCE: The Innovation Group and JLARC staff analysis of spending in other states.

NOTE: May not sum because of rounding. SB 1126 casino locations only. State revenue and costs only; does not include revenue or costs to localities or charitable gaming. a Other state taxes include personal income tax, sales tax, and corporate income tax. Projected revenue for casino gaming is estimated for 2025. b Sports wagering revenue presented for brick and mortar and mobile combined; all with a 12 percent tax rate in place. Sports wagering and online casino gaming tax revenue assumes fully mature market after five-year ramp up period. c Mid-point estimates of administration and oversight costs (assuming that role is filled by the Virginia Lottery.) Because of start-up costs, some gaming agency operational costs would occur before casinos or additional forms of gaming began producing revenue. A small portion of the estimated impact to lottery proceeds is attributable to HHR. d Includes state taxes paid on HHR gaming revenue and other state taxes generated by HHR operations such as sales and use taxes and personal income taxes paid by HHR employees. Does not include casino license fees, which could be substantial and used to offset a portion of agency operational costs.

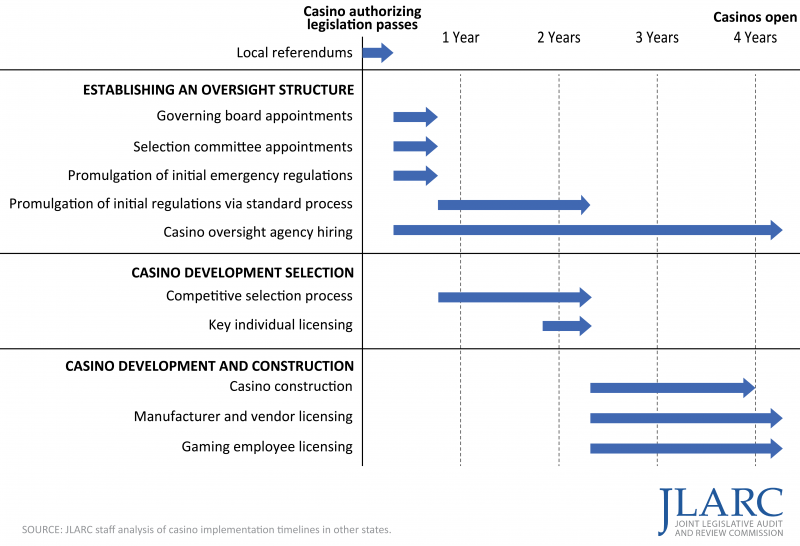

Casino development could take four years after authorization

Virginia casinos would likely open approximately four years after casino authorizing legislation passes if the process were similar to other states. Passing authorizing legislation represents the beginning of the casino development process. Following authorization in other states, authorized localities interested in hosting a casino have held popular referendums. Once at least one locality authorized gaming, states have undertaken activities that can be arranged broadly into three major phases: establishing the oversight environment, casino development selection, and casino development and construction. Chapter 10 outlines the key elements and decisions typically found in casino authorizing legislation.

Timeline for casino development

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

This JLARC report offers projections and considerations to be used when deciding whether to authorize and how to implement casino gaming or other additional forms of gaming. The report does not attempt to recommend whether Virginia should pursue additional forms of gaming, or what types of gaming should be pursued. However, the report does include several recommendations should the General Assembly choose to expand gaming in the Commonwealth.

Legislative action

- Establish a dedicated, stable funding source for problem gambling prevention and treatment, even if additional forms of gaming are not authorized;

- Include a requirement in any casino authorizing gaming legislation that:

- applicants for a casino license submit a responsible gaming plan as part of their application, and casino operators obtain accreditation for responsible gaming practices;

- casino licenses will be awarded through a competitive selection process, overseen by a designated committee whose members have experience in business finances and operations and represent state and local interests;

- an independent consultant, hired by the state, assess the accuracy and feasibility of casino development proposals; and

- owners and officers of any company vying for a casino operators’ license submit to and pass in-depth background and financial investigations.

The complete list of recommendations and options is available here.

The report included several online-only appendixes:

Appendix C: Technical methods

Appendix F: Lottery, chartiable gaming and horse racing in Virginia

Appendix G: Problem gambling literature review