Operations and Performance of the Virginia Community College System

Awarded a 2018 Certificate of Impact by the National Legislative Program Evaluation Society

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2016 the Virginia General Assembly directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) to review the Virginia Community College System (VCCS) (HJR 157). JLARC had not reviewed VCCS since 1991, despite notable changes in the system’s operations and mission. The study mandate specifically directs JLARC staff to review the usefulness and affordability of VCCS’s education and training, collaboration with other educational institutions, VCCS’s spending, and the adequacy of the support provided by the VCCS system office.

ABOUT VCCS

VCCS was created 50 years ago to improve Virginians’ access to higher education and prepare them for the workforce. The system comprises 23 separate colleges on 40 individual campuses, with numerous additional off-campus centers. The colleges offer hundreds of associate’s degrees and short- and long-term certificates. VCCS operates statewide but is governed centrally, and is the sixth largest state entity, in terms of total appropriations ($1.7 billion, FY16). In terms of enrollment, VCCS is the state’s largest institution of higher education, with a total enrollment of about 250,000 individual students.

WHAT WE FOUND

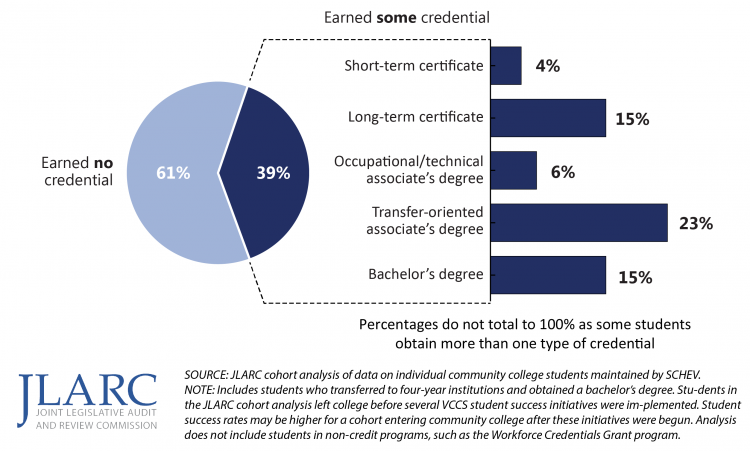

A relatively low percentage of community college students attain a credential

Community college students’ ability to earn credentials and degrees is important for the state’s economy and for ensuring that the state and families receive a return on the significant financial investment made in pursuit of a higher education. This study found that just 39 percent of Virginia’s community college students earned a degree or other credential, and this is also the case nationally. Moreover, community college students accumulate nearly a semester’s worth of excess credits by the time they earn a bachelor’s degree.

VCCS’s open enrollment policy is key to expanding access to higher education, but many students who enroll exhibit factors that challenge their ability to succeed. Compared to students at Virginia’s public four-year institutions, community college students are more likely to be older, part-time, low-income, the first in their family to attend college, and require remedial course work in English and math. These circumstances are associated with negative student outcomes, and could inform a system-wide strategy for prioritizing academic support services for at-risk students who could benefit from regular, more comprehensive, and even mandatory services, particularly academic advising.

Many students are not receiving needed advising services

According to the research literature, students who use academic advising are more engaged and more likely to complete a credential. To improve student outcomes, community colleges must provide more intensive—and in some cases, mandatory—academic advising services for students. Colleges should be more strategic about how they structure their advising programs and require mandatory advising for some students. However, Virginia’s community colleges do not have sufficient levels of staff to ensure that students receive the advising services that they need.

Majority of community college students did not earn a community college credential or bachelor’s degree

Dual enrollment programs do not appear to consistently save students time or money in their pursuit of bachelor’s degrees

The dual enrollment program is not clearly reducing the time or resources that students and the state invest in earning higher education credentials. Dual enrollment students take the same amount of time as non-dual enrollment students to earn a bachelor’s degree. The majority of dual enrollment students accumulate more credits than non-dual enrollment students to attain a degree.

Community colleges do not consistently ensure the quality of dual enrollment courses

Faculty and staff at some of the state’s four-year institutions expressed concerns about the quality of dual enrollment courses and a reluctance to accept them for credit. There are several recommended quality assurance practices that colleges could use, but none are used consistently. Implementing quality assurance practices could increase the likelihood that dual enrollment credits will be accepted by the state’s four-year institutions.

Transfer process and resources are difficult for students to use

Transfer students who earned a bachelor’s degree took longer and earned more credits than their counterparts who started college in a four-year institution. Transfer agreements between the state’s community colleges and four-year institutions have proliferated, are not kept up to date, and are not sufficiently accessible to students, making them difficult for students to understand and leverage. Streamlining transfer agreements and making them more accessible could improve the likelihood that Virginians who choose to pursue a bachelor’s degree by starting first in community college will save time and money.

Continuing increases in community college tuition and fees may diminish affordability

VCCS is currently an affordable option for Virginians to pursue higher education, and the majority of students do not incur debt to finance their education. However, VCCS tuition and fees have grown from six percent of per capita disposable income to nearly 11 percent in the past 10 years. Ensuring affordability is a critical responsibility of the State Board for Community Colleges, and it should receive more comprehensive information about how proposed increases in tuition and fees will impact affordability, enrollment, and student success.

VCCS campus locations ensure access to college courses and training, but viability of smallest campuses should be examined

VCCS has a relatively efficient structure compared to community college systems in other states, as measured by the number of colleges per capita and enrollments per college. VCCS also appears to have a sufficient number of colleges and campuses to adequately serve the state’s population, and there do not appear to be any colleges or campuses that should be closed or consolidated at the present time. VCCS has no formal process for considering closure or consolidation, but it should develop one to ensure that the need for closure or consolidation can be examined periodically.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Require each public four-year institution to (i) report to the State Council for Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) and VCCS on how dual enrollment courses transferred to their programs, (ii) develop a detailed description of the community college course work that will be credited to specific programs, (iii) maintain up-to-date transfer agreements, and (iv) annually provide new and revised agreements to VCCS.

- Require SCHEV to annually identify the college programs with the poorest transfer student outcomes.

-

Require VCCS to maintain a single repository for all transfer agreements.

Executive action

- Develop a proposal for identifying high school students who are not prepared for college-level course work and actions that could be taken to improve college readiness.

- Develop standard criteria that colleges can use for identifying students who are at risk of not succeeding in community college and a standard policy for colleges to follow to ensure that the most at-risk students receive proactive, individualized, mandatory academic advising and other academic services.

- Require colleges to use recommended quality assurance practices for dual enrollment courses and disclose more information about the transferability of dual enrollment courses.

- Present additional information to the State Board for Community Colleges to improve the board’s ability to consider the impact of tuition increases on affordability.

- Develop a formal policy and criteria for periodically examining the need to close or consolidate colleges or campuses.

The complete list of recommendations is available here.