Virginia's State Psychiatric Hospitals

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2022, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission directed staff to review the inpatient psychiatric hospitals operated by the state.

ABOUT VIRGINIA'S STATE PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS

The state operates nine psychiatric hospitals across Virginia, which provide psychiatric treatment services to individuals who are a threat to themselves or others because of mental illness. State hospitals also serve individuals in the criminal justice system, including jail inmates who require inpatient psychiatric treatment and defendants who need inpatient treatment to be able to understand the criminal charges against them. In FY23, about 5,000 individuals were admitted to state psychiatric hospitals, and the largest proportion were under a civil temporary detention order.

WHAT WE FOUND

Virginia’s state-run psychiatric hospitals face numerous challenges to effectively treating patients with especially acute psychiatric needs, and one of the greatest challenges is recruiting and retaining staff willing to work in an unpredictable environment that poses personal safety risks daily. The state psychiatric hospital work environment is difficult for nursing and clinical staff, but also the many support staff who are integral to hospital operations. Despite the difficulties inherent in working in such an environment, it is clear that state psychiatric hospital employees are highly committed to providing effective care to patients and providing needed support to their colleagues.

State psychiatric hospitals’ lack of control over their admissions jeopardizes patient safety

Around half of Virginia’s state psychiatric hospital patients are individuals from the community who have been determined to be a threat to themselves or others as a result of a mental illness (i.e, civil patients) and have been admitted involuntarily. Since 2014, state law has required state hospitals to admit individuals who magistrates have placed under a temporary detention order (TDO) if no other placement can be found for them. The legislation was intended to ensure that individuals in need of acute psychiatric services receive treatment, and it removed state hospitals’ ability to deny admissions. Since then, state hospitals have experienced significant ongoing capacity constraints and have regularly admitted more patients than they can safely accommodate

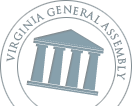

During FY23, seven of the nine state hospitals filled 95 percent or more of their staffed beds, and three regularly filled 100 percent of their beds. According to industry standards, inpatient psychiatric hospitals should not exceed 85 percent of staffed bed capacity to maintain a safe environment. Operating at higher occupancy levels limits hospitals’ ability to respond to changing patient needs, such as moving patients to a different room or unit if needed to protect their safety, or protect the safety of other patients and staff, because there is no available extra space. Additionally, being responsible for so many patients limits staff’s ability to intervene quickly and effectively in confrontations between patients or between patients and other staff.

All state hospitals have been regularly operating above the industry standard for safe operating levels

State hospitals also have seen an increase in the number of inappropriate admissions. If an individual has been determined to meet the criteria for a TDO, but does not actually have a condition that requires psychiatric treatment, statute still requires state hospitals to admit them, which is counterproductive for these individuals’ treatment and unsafe for them. These inappropriate admissions include individuals with neurocognitive disorders (i.e., dementia) and neurodevelopmental disorders (i.e., autism spectrum disorder), who accounted for 10 percent of state psychiatric hospital discharges in FY23. While they are a small percentage of state hospital patients, they stay for relatively long periods even though state hospital staff generally do not have the expertise to appropriately care for them. In addition, state psychiatric hospital staff frequently reported concerns regarding the safety and well-being of patients with neurocognitive and neurodevelopmental diagnoses.

Some state hospitals also have seen an increase in individuals who are dropped off by law enforcement before they are admitted, which is unsafe, especially for patients with urgent medical needs. Between FY22 and FY23, law enforcement dropped off 1,432 individuals at state hospitals before they were admitted. Some of these individuals were experiencing urgent medical needs, which state psychiatric hospitals are not equipped to treat. In January 2023, Virginia’s attorney general issued an official opinion concluding that law enforcement “dropoffs” at psychiatric hospitals are not permissible under state law. However, more than 450 individuals have been dropped off at state psychiatric hospitals since the issuance of that opinion.

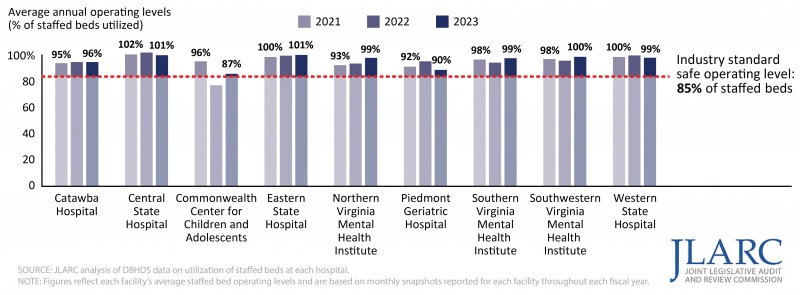

Many private psychiatric hospitals could admit more patients without exceeding safe operating levels

Underutilization of privately operated psychiatric hospital beds places an unnecessary overreliance on state hospitals and can delay or prevent individuals’ receipt of needed treatment. Neither state law, regulations, nor state licensing standards obligate private hospitals to accept any patient. However, greater utilization of privately operated hospitals would serve a clear public interest and meet a present and growing need to more quickly respond to Virginians who require inpatient psychiatric treatment, reduce the need for law enforcement to wait with patients who need involuntary treatment, and allow state hospitals to operate at safer levels. In FY23, 8,538 individuals under a civil TDO were on a waitlist for admission to a state psychiatric hospital, averaging around 700 individuals per month. Some of these individuals were never admitted to an inpatient facility for further evaluation or treatment, some were dropped off at a state hospital before being accepted by the facility, and some were arrested.

Private psychiatric hospital representatives have previously reported on underutilization of their inpatient psychiatric beds, and the majority of privately operated hospitals operate below the 85 percent staffed capacity level deemed safe for inpatient psychiatric facilities. If private psychiatric hospitals had used a portion of their unused staffed beds in FY22, enough patients would have been diverted from state hospitals to allow both state and private psychiatric hospitals to operate at a safe level.

About two-thirds of private psychiatric hospitals operated below 85 percent of staffed capacity (end of FY22)

Increase in forensic patients has significantly reduced beds available for civil admissions and exacerbated patient and staff safety risks

One reason for the current civil TDO waitlists is the growing number of forensic patients at state hospitals, who are criminal defendants a court has ordered to receive inpatient psychiatric evaluations and/or treatment. Increasing forensic patient admissions have affected all eight state hospitals for adults. Forensic admissions accounted for 47 percent of all admissions to state psychiatric hospitals in FY23. In addition, forensic patients remain hospitalized for about three times longer than civil patients, on average, so increased forensic admissions have substantially reduced state hospital bed capacity for civil admissions, and this trend is expected to continue. Moreover, because the costs of serving forensic patients cannot generally be billed to Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial insurance, growing forensic admissions has increased the state’s costs to operate state psychiatric hospitals.

The largest percentage of forensic patients are pre-trial defendants who judges find to be incompetent to stand trial and who must receive services to restore their competency. While many defendants receive outpatient competency restoration services, the majority receive these services on an inpatient basis at the state’s psychiatric hospitals. State hospitals have delayed admitting some defendants for competency restoration because of capacity limitations, creating risks that the state will be sued for violating defendants’ due process rights, which has happened in at least 16 states. In Virginia, from March through July 2023, 508 defendants were delayed admission to state hospitals for competency restoration. The other categories of forensic patients at state hospitals include individuals in jails or correctional centers who are determined to need inpatient psychiatric treatment under a TDO and individuals found not guilty by reason of insanity.

If state hospitals remain the only inpatient setting for treating forensic patients and no other action is taken to prioritize who is admitted for competency restoration, the capacity pressures they place on state hospitals are likely to worsen. This increasing forensic patient population exacerbates existing staff and patient safety risks because some forensic patients can be especially aggressive, according to state hospital staff. This is particularly concerning in state hospitals that mix civil and forensic patients in the same treatment unit or in the same room.

State hospitals are difficult to staff because of the unsafe working environment and uncompetitive pay for some positions

Statewide turnover across all state hospitals was 30 percent in FY23—over twice as high as the overall state government turnover rate. High turnover rates among state psychiatric hospital staff are a longstanding problem, but turnover has worsened over the past decade. As turnover has increased, positions have become more difficult to fill, leading to higher vacancy rates. The total state hospital staff vacancy rate doubled between June 2013 and June 2022 from 11 percent to 23 percent.

State hospital staff conveyed on a JLARC survey and through interviews that their facilities do not have enough staff to provide adequate care for patients. The majority of nursing and clinical staff responding to a JLARC survey observed their hospitals were insufficiently staffed. Twenty-eight percent of nursing and clinical staff reported that they usually lack enough time to give patients the attention they need, and this was especially common among social workers, case managers, and psychologists.

Virginia does not have specific staffing standards for either its state or privately operated psychiatric hospitals, and there is no industry consensus or federal requirement regarding the ratio of direct care staff to psychiatric hospital patients. A 2022 workgroup composed of chief nurse executives from Virginia state psychiatric hospitals determined a minimum staffing standard for nursing staff, but only one hospital meets that standard, and DBHDS has set a staffing goal below the workgroup’s recommendation because of funding constraints.

Most state psychiatric hospitals have increased their use of temporary contract staff to fill vacant positions, raising state hospital operating costs. On a per-staff basis, contractors are much more expensive—between two and three times the cost—than nurses and clinicians employed directly by the facility. In FY23, state hospitals spent at least 9 percent of their operating budget on contract staff ($47 million), 13 times the amount spent in FY13. The amount of total state hospital employee compensation spent on overtime more than tripled over this same time period, from $5.8 million in FY13 to $20 million in FY23. Combined overtime and contracting costs ($67 million) are more than six times higher than the previous decade.

Some state hospital roles are compensated at less-than-competitive rates, but working conditions also contribute to staffing shortages. Positions that were benchmarked to have the least competitive pay compared with the regional median pay were psychologists, social workers, housekeeping staff, and food services staff. While pay increases should be considered, pay is not the only factor making state hospitals difficult to staff. These facilities are some of the most physically dangerous work environments in all of state government; state hospitals have seven times the rate of successful workers’ compensation claims as employees in other state government agencies.

In addition to frustrations with pay and concerns over personal safety, state hospital nursing staff reported dissatisfaction with their hospital’s shift schedules. One in four registered nurses who predicted that they would leave their jobs in the next six months cited scheduling as a top reason they were planning to leave. In particular, state hospital leadership and staff expressed frustration with their hospital’s inability to offer 12-hour shifts to their employees, which is a standard healthcare industry practice.

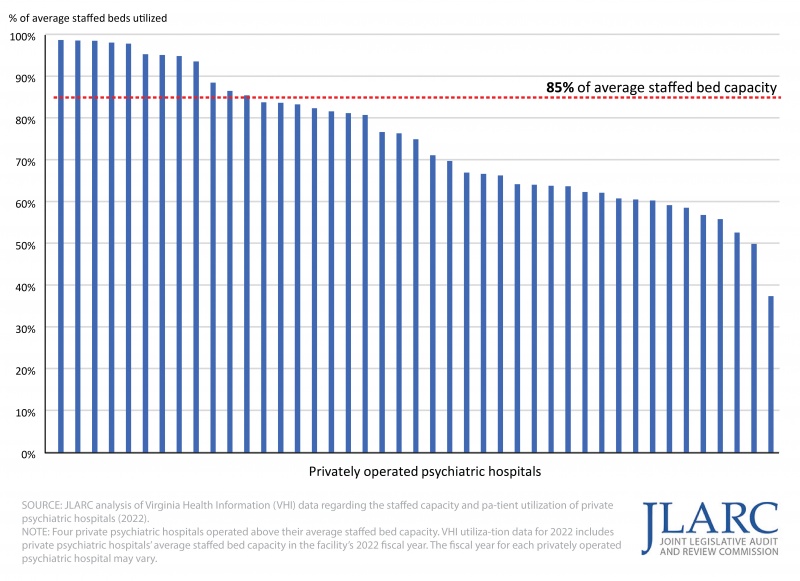

Patient safety is a concern, and some Virginia state hospitals use patient seclusion and restraint more often than other states

All hospitals had at least 20 percent of their staff report that they did not believe that their hospital was a safe place for patients, and staff commonly attributed this belief to high numbers of aggressive patients, increasing numbers of forensic patients, and the admission of patients with neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive disorders. There were about 7,400 known patient-on-patient physical incidents at state hospitals between January 2022 and May 2023 and 1,800 incidents of reported self-injurious behaviors. Across all of these incidents, over 1,400 resulted in patient injuries.

Rates of reported patient-on-patient physical incidents

(Jan. 2022 to May 2023)

State hospital staffing shortages and facility deficiencies, including weaponizable facility features, complicate state psychiatric hospitals’ efforts to maintain a safe environment. Most state psychiatric hospitals were not originally designed as inpatient psychiatric hospitals, and various facility deficiencies contribute to safety incidents and hinder staff’s ability to keep patients safe. Examples of facility deficiencies include ceramic tiles that can be removed and used as weapons; features like door handles and hinges that present risks to patients intent on harming themselves; hidden alcoves or poor lines of sight; shared rooms at seven hospitals, with at least two hospitals able to accommodate up to four patients in the same room; and lack of modern response mechanisms at four hospitals, which makes it more difficult for staff to efficiently de-escalate aggressive patient behavior or intervene quickly when patient incidents occur.

The use of seclusion and restraint is particularly high at some hospitals, and staff have reported that they and their colleagues are not well trained on how to properly use these methods or respond to patient aggression. State regulation requires all DBHDS-licensed and operated hospitals to use seclusion and restraint only as a last-resort intervention during an immediate crisis, with limits on the length of time adults and children can be subjected to either. Five of the nine state hospitals used higher rates of restraint relative to the national average. Six of the nine state hospitals used seclusion at higher rates than national averages. The Commonwealth Center for Children and Adolescents (CCCA) restrains patients at a higher rate than any other state hospital and over 20 times higher than the reported national average. CCCA patients also generally spend a longer amount of time continuously in restraints compared with other hospitals. DBHDS central office made efforts in 2023 to reduce the use of restraint at the facility, including leadership changes and greater attention to de-escalation methods used by staff.

OSIG receives hundreds of complaints but independently investigates only a relatively small portion of them

State hospital staff have unmatched visibility into patients’ care and potential safety risks, including possible violations of their personal safety or human rights. However, state hospital staff do not uniformly feel comfortable reporting patient safety concerns to their supervisor or hospital leadership. An independent complaint investigation process is critical to ensuring that patients, visitors, staff, or others have a safe and non-threatening means to raise concerns and can be confident that the investigation of their complaint will have integrity and lead to the proper resolution. The General Assembly has identified this need and assigned Virginia’s Office of the State Inspector General (OSIG) to receive and investigate complaints about patient care and safety at state psychiatric hospitals.

OSIG’s approach to handling complaints that it receives does not ensure that complaints are independently or thoroughly investigated, counter to the General Assembly’s intent. In FY23, OSIG received 633 complaints about DBHDS facilities, but referred most of them back to DBHDS and state hospitals to investigate. OSIG itself reviewed just 117 of those complaints. Independent investigation of complaints regarding patient safety is essential because referring complaints made to OSIG back to DBHDS and the hospitals could result in complaints not being investigated thoroughly or, worse, being purposely ignored or concealed. It also makes it less likely that appropriate and effective remedies and sanctions will be pursued.

Independent review of a sample of patient records concluded that most sampled patients received satisfactory care, but there were exceptions

The quality of patient care can affect the likelihood of their readmission to an inpatient setting after discharge. Over the past decade, about one in five adults and one in four children discharged from a state psychiatric hospital under a civil status were readmitted within six months. Psychiatrists at VCU Health conducted an independent review of state hospital patient charts for this study. Psychiatrists collectively concluded that most patients in the sample appeared to have received satisfactory care, but there were exceptions. For example, VCU psychiatrists reported concerns about the medication given to 17 of the 45 patients from the sample who received medications during their hospitalization, including the dosage, appropriateness of the medication for the patient’s diagnosis, or adverse side effects. In several instances, reviewers noted concerns about the use of multiple medications simultaneously. Reviewers also observed little documentation by doctors or psychiatric nurse practitioners about the patient’s progress or their visits with the patient.

During JLARC staff’s visits to the state psychiatric hospitals, staff at several hospitals pointed out deficiencies in the hospitals’ physical space that they believed hindered the hospital’s ability to provide optimal patient care and treatment. For example, hospital staff highlighted that in some hospitals, there is not enough space to offer small group therapy sessions as often as needed.

Psychiatric hospital for children and youth has persistent operational and performance issues

CCCA is intended to be the facility of last resort for youth experiencing a severe mental illness and who are a threat to themselves or others. However, persistent operational and performance issues at CCCA justify considering whether CCCA should continue to operate. Through various metrics, CCCA stands out as the worst or among the worst performers compared with other state hospitals. For example, it has the highest rate of patient-on-patient and patient-on-staff physical safety incidents, the highest rate of patient self-harm, the highest number and percentage of substantiated human rights complaints, the highest use of physical restraint against patients, the highest staff turnover, nearly the highest staff vacancy rate, and the greatest dependence on expensive contract staff. In a recent unannounced inspection by a national accrediting agency (the Joint Commission), CCCA received 28 citations and was determined to be an immediate threat to the health and safety of patients, according to DBHDS.

CCCA has become more costly to operate, neither patient outcomes nor staffing challenges have improved, and additional investment in the facility is unlikely to result in further improvements. Additionally, most other states do not operate a youth psychiatric hospital.

DBHDS should develop a plan to close CCCA and find or develop alternative placements for the patients who would otherwise be placed there. Following approaches used in other states, including those that do not operate a state hospital for children, the state should contract for services that would better meet the needs of CCCA patients, including private psychiatric hospitals, residential crisis stabilization units, and residential psychiatric treatment facilities, and that are closer to their home communities. State funds used to operate CCCA, about $18 million in FY23, could instead help fund placements for youth who would otherwise be admitted there. If CCCA were closed, at any given time the number of youth needing an alternative placement, such as at a private psychiatric hospital, a crisis stabilization unit, or residential psychiatric treatment facility, would be relatively low (two youths per day, on average).

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

The following recommendations include only those highlighted for the report summary. The complete list of recommendations is available here.

Legislative action

- Exclude behaviors and symptoms that are solely the manifestation of a neurocognitive or neurodevelopmental disorder from the definition of mental illness for the purposes of TDOs and civil commitments so that they are not a basis for placing an individual under a TDO or involuntarily committing them to an inpatient psychiatric hospital, with an effective date of July 1, 2025.

- Grant state psychiatric hospitals the authority to deny admission to an individual under a TDO or civil commitment if the individual’s behaviors are solely a manifestation of a neurocognitive or neurodevelopmental disorder and the individual does not meet the criteria for inpatient psychiatric treatment, with an effective date of July 1, 2025.

- Direct the secretary of health and human resources to evaluate the availability of placements for individuals with neurocognitive or neurodevelopmental disorders and identify and develop strategies to support these populations, including through enhanced Medicaid reimbursements or Medicaid waivers, and report results by October 2024.

- Grant state psychiatric hospitals the authority to delay the admission of an individual until it has been determined that they do not have urgent medical needs that the hospital cannot treat.

- Require the commissioner of the Virginia Department of Health to condition the approval of any certificate of public need (COPN) for a project involving an inpatient psychiatric facility on the applicant’s agreement to admit individuals who are under a civil TDO.

- Provide funding to assist privately operated hospitals with accepting more individuals under a TDO and with discharging patients who face substantial barriers to discharge.

- Grant state psychiatric hospitals the authority to decline admission to an individual under a TDO if doing so will result in the hospital operating in excess of 85 percent of the hospital’s staffed capacity, with an effective date of July 1, 2025.

- Provide salary increases for social workers, psychologists, and housekeeping and food services staff.

- Direct the Department of Human Resource Management to allow state hospitals to define nursing staff who work 36 hours per week as full-time staff to facilitate hospitals’ ability to use 12-hour shifts.

- Create and fund the number of nursing positions DBHDS has determined are needed to provide quality care at the state’s psychiatric hospitals.

- Direct OSIG to develop and submit a plan to fulfill its statutory obligation to fully investigate complaints of serious allegations of abuse, neglect, or inadequate care at any state psychiatric hospital, and develop and submit annually a report on the number of complaints it has received and fully investigated.

- Direct DBHDS to develop a plan to close CCCA and find or develop alternative placements for children and youth.

Executive action

- Virginia Department of Health should develop and implement a process to determine whether all providers granted a COPN based at least partially on their commitment to accept patients under a TDO are fulfilling this commitment and take appropriate remedial steps to bring them into compliance with this commitment, if necessary.

- DBHDS should seek clarification from the Office of the Attorney General regarding whether the DBHDS commissioner has the legal authority pursuant to 12VAC35-105-50.B to require providers of inpatient psychiatric services to admit patients under a TDO or civil commitment if the provider has the capacity to do so safely.

- DBHDS should formally solicit proposals from state-licensed psychiatric hospitals or units in Virginia to admit certain categories of forensic patients and work with those hospitals that respond to develop a plan and timeline to contract with them to admit forensic patients.

- DBHDS should study and propose designating certain state psychiatric hospitals or units within them as appropriate to treat only forensic patients.

- DBHDS should contract with a subject matter expert to assess the therapeutic environment for each state psychiatric hospital, prioritizing those with the highest rates of seclusion and restraint.

- DBHDS should develop and implement a process to conduct regular reviews of a sample of state psychiatric hospital patient records to evaluate the quality of care they provide, including procedures for holding hospitals accountable for correcting factors that are determined to cause the delivery of ineffective, unsafe, or generally substandard patient care

The complete list of recommendations is available here.