Virginia's K-12 Teacher Pipeline

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2022, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) directed staff to review the adequacy of the supply of qualified K–12 teachers in Virginia.

ABOUT VIRGINIA'S K-12 TEACHER PIPELINE

Virginia’s “teacher pipeline” consists of the programs and processes that attract, prepare, license, recruit, and retain public K–12 teachers. While the Commonwealth’s 134 local school divisions individually recruit and retain teachers, the state plays a role in the teacher pipeline through higher education institutions that administer teacher preparation programs, VDOE’s licensure of teachers, and funding for initiatives to promote the teaching profession.

WHAT WE FOUND

Statewide, teacher vacancies and reliance on less than fully licensed teachers has increased

Having enough, high quality teachers is among the most important factors necessary for a quality education system. The latest available data shows continued declines in the number of teachers in Virginia’s K–12 system and the proportion of them who are fully licensed:

- 4.5 percent of teaching positions were vacant at the start of the 2023–24 school year, up from 3.9 percent in the prior school year (and less than 1 percent in years prior to the pandemic); and

- 16 percent of Virginia’s teachers were not fully licensed or not teaching “in field” in SY2022–23, up from 14 percent in the prior school year (and 6 percent a decade ago).

Some divisions are facing substantial teacher workforce problems, but other divisions are not

The severity of the teacher workforce problems varies widely across the state. Some divisions have much higher than average teacher vacancy rates, while others have very few or no vacant teaching positions. Virginia school divisions with large populations of Black students have especially high teacher vacancy rates.

As with vacancies, school divisions’ reliance on teachers who are not fully licensed varies widely. For example, two divisions reported that all their teachers were fully licensed, while two reported that only about half of their teachers were. Similarly, two divisions reported that all their teachers were teaching “in field,” while two reported only about two-thirds of their teachers were.

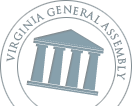

Direct pathways to licensure tend to better prepare teachers to be successful in the classroom

In general, teachers who use direct pathways to become a fully licensed teacher are better prepared for the classroom. The most common direct pathway by far in Virginia is graduating from a traditional higher education teacher preparation program as a fully licensed teacher. Traditional higher education-based preparation programs prepare about 2,600 teachers annually in Virginia. These programs include important components of effective teacher preparation, including pedagogical coursework, student teaching and mentorship from experienced teachers, and college-level subject area coursework.

School divisions believe traditional higher education preparation programs better prepare people to teach than indirect pathways. For example, 46 percent of school divisions surveyed by JLARC reported that provisionally licensed teachers are very poorly or poorly prepared to be teachers, while only 3 percent of school divisions reported poor preparation among individuals who attended traditional higher education preparation programs.

Teacher residency programs also produce well prepared teachers. Residency programs involve an extended co-teaching placement while simultaneously completing coursework. Residency programs have a rigorous design and are low cost to participants because of the financial assistance provided. Residency programs, though, are expensive to administer and currently have limited capacity in Virginia. State-supported residency programs prepared just under 100 individuals for teaching in SY2022–23.

In January 2023, VDOE initiated a registered teacher apprenticeship program. VDOE has distributed funds to six partnerships between school divisions and higher education institutions to implement programs. Apprenticeship programs can produce teachers that are well prepared, according to experts. They also pay individuals during their preparation and have the advantage of being able to use federal workforce funds to cover a portion of program costs. If implemented effectively, Virginia’s new registered apprenticeships should result in additional well-prepared teachers without the financial barriers associated with traditional preparation.

Indirect pathways give individuals flexibility to obtain credentials over time and cost less

In recent years, an increasing number of individuals have been entering teaching through Virginia’s indirect pathways to fill current teacher vacancies. These indirect pathways include provisional licensure, career switcher programs, and division-led preparation programs. Individuals using these pathways to become a teacher are typically less well prepared in the short term, but can move through those pathways at substantially less cost and benefit from more flexible pacing and delivery format (figure, next page). For example, most provisionally licensed teachers take required courses at their convenience, often online, while working as a teacher. Tuition can still be costly for these courses, but many divisions offer tuition reimbursement for provisionally licensed teachers, and several divisions offer in-house preparation at no cost to participants.

Teacher pathways have tradeoffs between quality and affordability

Virginia-specific assessment required for traditional teacher preparation programs may be an unnecessary barrier

A Virginia-specific test (which is separate from the nationally used and recognized Praxis subject assessments) is preventing some individuals from enrolling in and completing traditional higher education teacher preparation programs. The Virginia Communication and Literacy Assessment (VCLA) is a Virginia-specific test with two subtests that measure reading comprehension and written communication skills. While 86 percent of test takers eventually pass the VCLA, an average of about 630 test takers (14 percent) did not pass it each year over the last six years.

The VCLA may present an unnecessary barrier to admission to or completion of traditional teacher preparation programs when the state needs more people to enter the teacher pipeline. According to staff at 11 of the 14 Virginia public teacher preparation programs, failure to pass required assessments such as the VCLA is a top reason individuals are unable to enroll in and/or complete preparation programs. The test, which was developed in 2007 and has not been updated, is outdated and tests prospective teachers on skills that are not relevant for some types of teachers to be effective.

Tuition, assessments, and unpaid student teaching present financial barrier to some participants in traditional preparation programs

Costs associated with traditional higher education teacher preparation programs are another barrier to participation in these high quality programs. Seventy-three percent of new teachers surveyed by JLARC who attended traditional preparation programs reported at least one cost associated with preparation (tuition and fees, cost of licensing tests, unpaid student teaching) to be a moderate or significant barrier to completing their preparation program. In addition, staff from 10 of the 14 traditional preparation programs at Virginia’s public higher education institutions cited financial concerns as a top reason why teacher candidates did not enter or complete their program.

Virginia has a relatively small ongoing program to reduce the cost of tuition for traditional teacher preparation for some students. The Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program (VTSLP) awards up to $10,000 for tuition and fees to teacher candidates at public or private institutions pursuing teaching in a critical shortage discipline or who are minority teacher candidates. The program requires recipients to teach for at least two years in the critical shortage discipline or in a school where more than half of the students are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

Recently, $708,000 in annual VTSLP funding has facilitated scholarship loans to 75 recipients per year. This represents an estimated 10 percent of all graduates of Virginia’s traditional teacher preparation programs who have financial need (based on Pell grant eligibility). Higher education teacher preparation programs report there is substantially more demand for this program than current funding levels support. For example, one large public institution reported having at least 50 additional individuals eligible for scholarship loans every year who were not able to receive them.

Licensure requirements and process can seem complex and be unclear to some applicants

School division HR staff surveyed by JLARC expressed mixed opinions on how clearly defined the requirements are to obtain a Virginia teaching license. Thirty-six percent of division staff “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” that teacher licensure requirements are sufficiently clear. When asked on a JLARC survey, one new teacher said: “The process to apply for a license is so complicated and draining.”

The lack of clarity about licensure requirements can be especially challenging for teachers with provisional licenses and fully licensed teachers in other states interested in teaching in Virginia. VDOE does not publish information specifying which courses meet licensure requirements. As a result, provisionally licensed teachers may take courses that do not fulfill Virginia’s licensure requirements, which can be costly and delay their ability to teach. Similarly, VDOE does not publish information on the specific license types and endorsement areas that are comparable between Virginia and other states. As a result, teachers from another state seeking a Virginia license must submit a full application to VDOE to learn whether their license and/or endorsement area will be accepted.

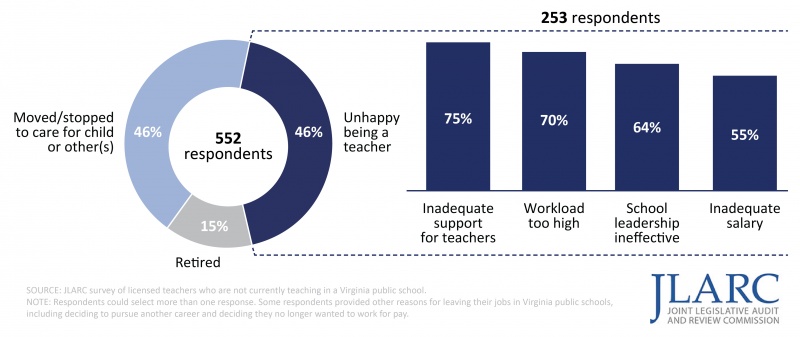

Factors other than barriers to preparation program participation and the licensure process are primary reasons for state’s teacher shortage

Though the state can improve the teacher preparation and licensure processes, Virginia’s teacher shortage will not materially improve until the root causes of the shortage are addressed. Teachers in Virginia have left the profession primarily either for personal reasons (e.g., family moving to another location), or because they were unhappy with the job. Inadequate support for teachers generally, high workload, ineffective school leadership, and low salary are the top reasons cited for their unhappiness with being a teacher (figure), according to a JLARC survey.

Reasons licensed teachers left positions in Virginia public schools

Other, recent JLARC reports have recommended ways to address issues related to teacher support and workload (e.g., more instructional assistants), and salary (e.g., changing the SOQ formula inputs to more accurately reflect actual teacher salaries). Therefore, the potential benefits of the recommendations and policy options in this report related to the teacher pipeline must be considered in the context of these broader factors that more heavily influence teacher recruitment and retention.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Authorize a waiver that allows higher education teacher preparation programs to recommend qualified individuals who have not passed the VCLA to receive full teacher licensure.

- Increase funding for the Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program.

Executive action

- Replace the VCLA with a relevant and nationally recognized test, or remove it as a requirement for full teacher licensure.

- List on the VDOE website the (i) courses that fulfill licensure requirements in each endorsement area for provisionally licensed teachers pursuing full licensure and (ii) license types and endorsement areas that qualify for reciprocity with selected other states.

- Report on the program participation, size, and funding levels of the new registered teacher apprenticeship program.

The complete list of recommendations is available here.