Affordable Housing in Virginia

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2020, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission directed staff to conduct a review of affordable housing in Virginia. JLARC staff were asked to report on the number of Virginia households that are housing cost burdened; the supply of affordable quality housing statewide and by region; the state’s efforts to increase the supply of affordable housing and make existing housing more affordable through direct financial assistance; and the effectiveness of the management of the state’s housing assistance programs.

ABOUT VIRGINIA'S AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROGRAMS

Most programs to improve housing affordability subsidize either the construction or rehabilitation of housing units to increase the inventory of affordable housing or provide financing or direct cash assistance to households to help them afford housing costs. Virginia’s housing programs are funded with federal, state, and local funds. The Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development is the lead state agency for housing programs, and Virginia Housing is the state’s housing finance agency.

WHAT WE FOUND

Virginians most affected by the lack of affordable housing are renters, have low incomes, are more likely to live in the state’s populated areas, and often work in common, essential occupations

Households are considered housing cost burdened when they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing expenses. Housing cost burden constrains households’ budgets, making it difficult for households to afford

other necessities and making eviction more likely. Approximately 29 percent of Virginia households (905,000) were

housing cost burdened in 2019, and nearly half of these households spent more than 50 percent of their income

on housing. Virginia ranks near the middle of states in terms of the percentage of households that are cost burdened.

Households that rent their homes are more likely to be cost burdened than households that own their homes. Approximately 44 percent of renting households are cost burdened compared with 21 percent of owning households.

The prevalence of housing cost burden among low-income Virginians has increased slightly over the last decade

to 63 percent. This affects Virginians who work in common occupations and who are paid relatively low salaries,

such as home health aides ($22,000 salary), teaching assistants ($29,000 salary), bus drivers ($45,000 salary), and social workers ($51,000 salary). These workers are needed in all parts of the state, and a lack of affordable housing in

some regions constrains the supply.

The majority (67 percent) of cost-burdened households live in the state’s most populated regions: Hampton Roads, Northern Virginia, and Central Virginia. Households in Hampton Roads are more likely to be cost burdened than in any other region in the state. Black and Hispanic households are more likely to be cost burdened than white

households.

Declining number of Virginians can afford to buy a home, and state has a shortage of at least 200,000 affordable rental units

Rising home prices have made it more difficult for Virginians to own their homes. The median home sales price in Virginia has risen 28 percent over the past four years to $270,000 in 2021. Virginia’s stock of homes that would be affordable to low- and middle-income households has declined substantially in the past few years. According to

the Virginia Realtors Association, the percentage of all Virginia homes sold for $200,000 or less has decreased by 40 percent since 2019.

Low- and middle-income households may have incomes that could support mortgage payments but lack the savings to cover the upfront costs of purchasing a home. Rising home prices mean that down payments and closing costs can be over $10,000 on even moderately priced homes.

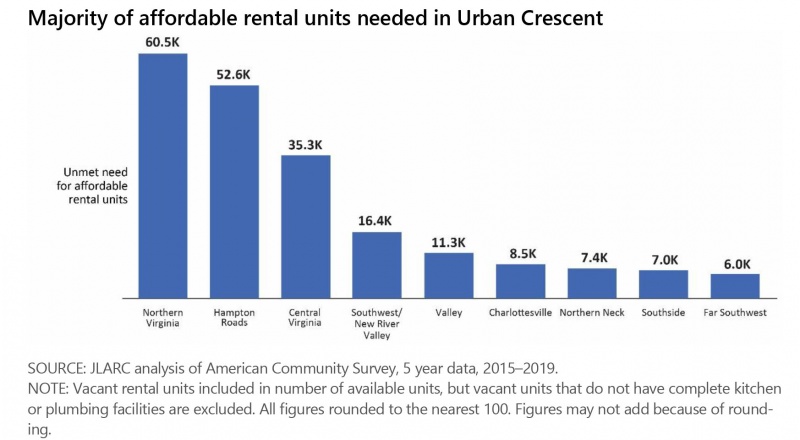

Renting a home can help households avoid the upfront costs of purchasing a home, but Virginia has a statewide shortage of at least 200,000 affordable rental units for extremely and very low-income households. Every region in the state has a shortage of affordable rental units, but Northern Virginia and its bordering regions need the largest number of affordable rental units—almost 80,000.

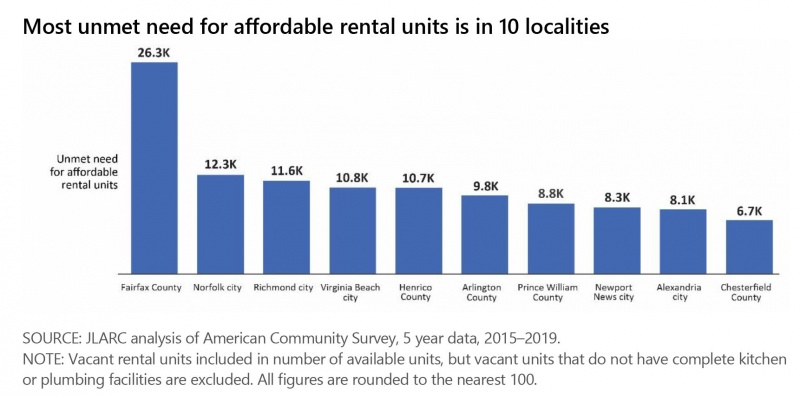

Ten localities with the largest need for affordable rental units account for over 50 percent of the state’s need for affordable rental units and have experienced relatively high population growth. Four of these localities are in Northern Virginia, three are in Hampton Roads, and three are in Central Virginia.

Addressing statewide needs for affordable housing through direct cash assistance and construction of new housing would be very costly

Addressing the state’s housing needs will require a substantial investment of time and money guided by a strategic and prioritized plan of action. Providing direct assistance to all cost-burdened households who have extremely or very low incomes could cost as much as $5 billion annually. Providing housing assistance payments to extremely

and very low-income cost-burdened renters and households experiencing homelessness could cost as much as $3.7 billion annually. Providing housing assistance payments to extremely and very low-income cost-burdened homeowners could cost up to $1.3 billion annually. In addition to providing direct cash assistance to households, state assistance is needed to create additional affordable rental units, but meeting the existing need through new construction would likely require several years. The annual cost to develop 20,000 units per year, which could meet the statewide need after 10 years, could be approximately $1.6 billion.

Virginia Housing could contribute more to the state’s largest source of discretionary funds to expand affordable housing access

Virginia Housing reinvests a portion of its net income into a program to expand access to affordable housing, Resources Enabling Affordable Community Housing (REACH). Since 2014, Virginia Housing has contributed over $550 million to REACH and currently commits 60 percent of its net income to the program annually. Because funding for REACH is generated from Virginia Housing’s net income, the program is not subject to federal allocations, requirements, or rules, and the funds can be used flexibly to best address the state’s most pressing housing needs.

Virginia Housing spends REACH funds for homeownership, rental housing, and community outreach. However, Virginia Housing tracks limited outcome and output measures for the program.

Virginia Housing has one of the highest net asset balances of any housing finance agency in the country at approximately $3.7 billion at the end of FY21 and could set aside more of its revenues for REACH. Currently, the formula the authority uses to determine the percentage of its net revenues to contribute to REACH unnecessarily

diminishes its REACH contributions. By modifying how it factors REACH grant expenditures into the formula, Virginia Housing could potentially contribute $230 million more to REACH by FY31 than it would using the current formula. Additionally, Virginia Housing could afford to increase the percentage of net income allocated to

REACH to 75 percent. By modifying the REACH formula and increasing the contribution percentage, Virginia Housing could potentially contribute $332 million more to REACH by FY31 than it otherwise would.

Virginia Housing has invested substantially in new affordable multifamily housing but could do more to address the need for affordable rental housing

Since 2013, Virginia Housing has administered the majority of financing for new affordable housing developments—over $4 billion to 348 housing developments. (By comparison, the Department of Housing and Community Development [DHCD] has administered over $60 million to 87 housing developments.) Virginia Housing is

also the largest financer of the projects that it funds, averaging around 60 percent of the typical project’s financing. (By comparison, DHCD financing typically averages around 9 percent.)

Virginia Housing has significantly increased its investments in “workforce housing” development through taxable bond-financed loans and loan subsidies from its REACH program. However, workforce housing developments do not reduce housing costs for low-income residents, because these developments are not required to set rents below market rates. About 30 percent of workforce housing units are rented to low-income households, but rents for these units are similar to market rate rents in units in the same development. As a result, the median cost burden for

renters in these income-restricted units is greater than the statewide median cost burden for low-income renters. As many as half of these households are housing cost burdened even though these projects are supposed to be providing affordable housing for low income households.

Virginia Housing does not maximize two significant sources of funding that could be used to help finance more affordable multifamily rental developments—its multifamily rental REACH allocation and federal tax-exempt private activity bonds. These two resources could be used together to increase interest among developers to build

multifamily rental developments by offering gap funding that could potentially make additional affordable rental developments financially feasible. Using REACH and tax-exempt private activity bonds for affordable rental developments would draw down additional federal funding in the form of 4 percent low income housing tax credits.

Virginia Housing’s loan programs have helped finance home purchases for many households who would have had difficulty qualifying for a commercial mortgage

Virginia Housing’s homebuyers tend to have much lower incomes and are considered “higher risk” than borrowers acquiring loans on the commercial mortgage market. For example, the median gross income of a Virginia Housing borrower is $62,000, compared with the median gross income of about $88,000 for a Virginia borrower in the

commercial market. Virginia Housing borrowers also have more debt than commercial borrowers and are more likely to be first-time buyers than borrowers in the commercial mortgage market. Despite these riskier characteristics, Virginia Housing borrowers have lower foreclosure rates than commercial borrowers.

Virginia Housing could provide better assistance with upfront mortgage costs, and its mortgage interest rates are slightly higher than the commercial market

Virginia Housing also offers several types of assistance for the upfront costs of purchasing a home, and most of its borrowers receive such assistance. (DHCD also offers such assistance, but its programs are much smaller.) Virginia Housing’s most popular program is the “Plus Mortgage” (second mortgage) program, which allows homebuyers

to finance down payment and closing costs. While this program is beneficial to homebuyers in the short term, it substantially increases the borrowers’ debt and raises their mortgage interest rate.

State law requires Virginia Housing to establish mortgage interest rates that are as low as possible. Virginia Housing’s financing structure and costs to raise capital are similar to most other lenders, so Virginia Housing should generally have interest rates at least as low as commercial lenders. However, some Virginia Housing mortgage interest rates

are slightly higher than commercial mortgage interest rates. Virginia Housing’s practice of adding basis points to Plus mortgages is a key factor driving increased interest rates. While the resulting difference in monthly payments is small and does not result in borrowers paying significantly more interest on their loans, Virginia Housing should take steps to keep its single-family loan interest rates as low as possible.

Local zoning affects affordable housing supply, particularly in fast-growing localities

Addressing Virginia’s affordable housing shortage will require construction of new affordable housing, but local zoning ordinances can be a substantial barrier to such new construction. Localities design their own zoning ordinances, and overly restrictive ordinances can limit housing supply—especially affordable housing supply. Very

few localities zone more than 50 percent of their land for multifamily housing, which is the housing that is most needed in Virginia. Efforts to have a parcel rezoned for multi-family development can cost as much as $1 million. This can make financing a development with affordable rents cost prohibitive.

Zoning ordinances that allow multifamily housing projects help ensure that those projects are built at a lower cost, which may help keep rents lower. However, state policies on housing development proffers currently discourage localities from allowing housing to be developed without rezoning, because localities are eligible for proffer payments only when a parcel needs to be rezoned to meet the developers’ specifications.

Virginia does not effectively identify or plan for statewide affordable housing needs

Until recently, Virginia has not undertaken a comprehensive state-led effort to identify and plan for housing needs statewide. State officials need statewide, regional, and locality-specific information on housing needs to make informed decisions about how and where to deploy available resources. Depending exclusively on local governments’

own assessments is inefficient and makes it difficult to reliably compare needs across the state, pinpoint the state’s most acute housing needs, and prioritize state resources accordingly. Moreover, state funding investments in affordable housing should be informed by statewide needs and plans—similar to funding for transportation infrastructure, for example—rather than a collection of locality-specific assessments and plans. Many other states conduct regular evaluations of affordable housing needs and maintain a statewide plan for addressing them.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

- Amend the Code of Virginia to require that Virginia Housing-financed rental units set aside for low-income households charge rents that are affordable to households earning 80 percent and below area median income.

- Direct DHCD to evaluate how a grant program could be structured, funded, and administered to incentivize localities to adopt zoning policies that facilitate the development of affordable housing.

- Direct DHCD to conduct a statewide housing needs assessment every five years, develop a statewide housing plan every five years with measurable goals, and provide annual updates to the General Assembly on progress toward those goals.

Executive action

- Virginia Housing to adopt performance measures for its REACH program, revise the formula it uses to determine annual REACH contribution amounts to maximize contributions, increase the percentage of net income allocated to REACH, and report on use and impact of REACH to the General Assembly.

- Virginia Housing to use REACH to provide gap funding for multifamily rental projects that use tax-exempt private activity bonds and 4 percent low-income housing tax credits.

- Virginia Housing to review necessity of adding basis points to Plus Mortgages to minimize interest rates charged to low-income borrowers and present options to its Board of Commissioners for lowering its interest rates.

- Virginia Housing to replace its current down payment assistance programs for low-income borrowers with a larger down payment assistance grant or a 0 percent interest deferred second mortgage.

Policy Options for Consideration

- General Assembly could give additional localities the authority to require developers to set aside a portion of units to rent or sell below-market or pay a fee to the locality.

The complete list of recommendations and options is available here.